LANDMARKS

LANDMARKS: Cemeteries of Minnesota

2/14/2022 | 57m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Travel along with MN historian Doug Ohman and explore the fascinating world of Cemeteries.

Cemeteries are the last visible vestiges of our past. These sacred places hold our history and are clues to the stories worthy of remembering. By honoring those have gone before, this program celebrates life itself. Travel along with Minnesota historian Doug Ohman as he explores the fascinating world of Cemeteries. Doug will highlight Minnesotans that have a passion for these sacred grounds.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

LANDMARKS is a local public television program presented by Pioneer PBS

This program is made possible by contributions from the voters of Minnesota through a legislative appropriation from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and viewers like you.

LANDMARKS

LANDMARKS: Cemeteries of Minnesota

2/14/2022 | 57m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Cemeteries are the last visible vestiges of our past. These sacred places hold our history and are clues to the stories worthy of remembering. By honoring those have gone before, this program celebrates life itself. Travel along with Minnesota historian Doug Ohman as he explores the fascinating world of Cemeteries. Doug will highlight Minnesotans that have a passion for these sacred grounds.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch LANDMARKS

LANDMARKS is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

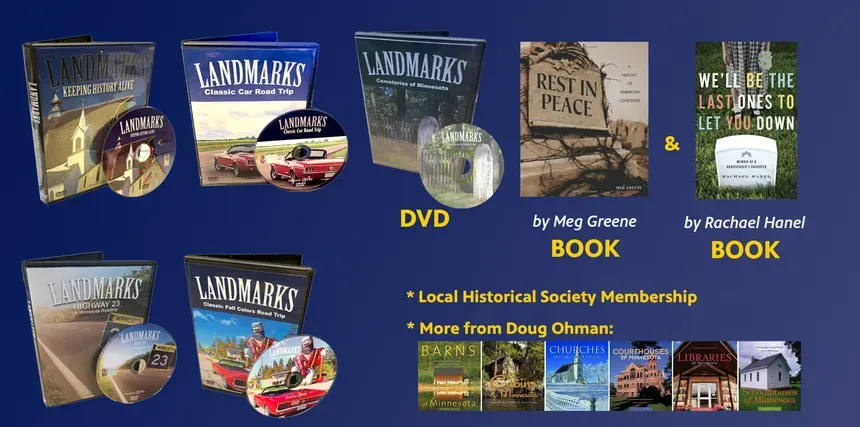

LANDMARKS Premium Gift Items

To order, email yourtv@pioneer.org or call 1-800-726-3178.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(soft upbeat music) - Hi friends, have you ever wondered about the stories, the history and the future of our cemeteries?

If so, you're not alone.

My name is Doug Ohman.

As a Minnesota historian, I find that cemeteries hold so much intrigue and of course, history.

They also carry so many memories.

Come along as we travel together throughout the state exploring.

We will meet people along the way that share in that same passion, their love for cemeteries.

(soft upbeat music) I like what American Patriot Benjamin Franklin said, "Show me your cemeteries and I will tell you "what kind of people you have."

Remember, cemeteries are a way of honoring those who came before.

As we look ahead into the future, it is so important to occasionally look back to the lives and memories of those who are here before us.

Many cemetery memorial stone have etched on them the words, gone but not forgotten.

(soft upbeat music) The human impulse to bury one's dead is as old as civilization itself.

In pre-European Minnesota, the dead were buried in methods that might seem different than today's practice but were traditions that were equally honoring.

Our state's earliest burial grounds were earthworks or mounds.

It has estimated that there are nearly 12,000 known burial mounds in Minnesota.

Many were undoubtedly destroyed without being recorded.

In Northern Minnesota, The Ojibwe used burial huts, otherwise known as spirit houses.

These traditional spirit houses had a small doorway that allowed loved ones to pass along food, tools or weapons that might help the deceased in the afterlife journey.

The houses were left to decay and become part of nature again.

In the native Dakota tradition, the dead were often elevated on scaffolding or in trees to protect them from roaming animals.

By the 1850s, Europeans began to move into what would soon become the nation's 32nd state.

As part of the American frontier, Minnesota attracted settlers and homesteaders from across the country and the world.

And soon there was a need for burial places.

Two of Minnesota's earliest cemeteries, Oakland in St. Paul and Pioneer & Soldier Cemetery in Minneapolis date back to the early 1850s.

Both of these cemeteries are good examples of the rural cemetery movement in Minnesota.

During the mid to late 1800s, Americans found themselves in an era of explosive industrial growth.

In both St. Paul and Minneapolis, the idea was to put the cemetery outside the city in the serenity of the country side.

The landscape was intended to offer a sense of calm.

In it, people could escape the city's dirt and noise and take in nature's gentle beauty.

It was that Pioneer that I had the privilege to spend some time learning some early history while talking with some cemetery historian, Susan Hunter Weir.

How old is pioneer cemetery?

- The first burial was 1853, so it predates Minnesota statehood.

One of the things that's kind of fun about it, it was the first cemetery listed in the National Register of Historic Sites, the first Minnesota as a free standing cemetery.

So the chapel Lakewood is Fort Snelling is part of a larger compound but just as a freestanding cemetery, it was the first and that speaks to its historic nature that if you walk around and you look at the markers, you can see, for example, you can trace the patterns of immigration.

In this particular area, of course, I always joke and say, we have 22,000 plus burials but 1035 of them are named Johnson.

But this really captures sort of the early immigration and in particular, at that time people were coming from Scandinavian countries, they were coming from Europe.

But it was also the burial place of choice for the early African-American community.

And one of the hallmarks of this cemetery is that it was never racially segregated and that the original owners, Martin and Elizabeth Layman were anti-slavery folks.

They went to the first Baptist Church of Minneapolis which was more or less the anti-slavery movement in Minneapolis at that time.

- You don't see the grand monuments here.

- Nope, I think that this is the place where most of our grandparents would be buried or great grandparents, right?

These are the people who worked in the flower mills, for railroads, the lumbering industry, the very things that put Minneapolis on the map.

- Why did the cemetery close?

- It was full.

There were 27,000 people buried here and it was privately owned.

They made no provision for perpetual care.

And so once it was filled, it just wasn't profitable anymore.

And it was really falling into disrepair.

- [Doug] So what year did it close?

- [Susan] It closed in 1919.

- [Doug] After 1919, Pioneer Cemetery has had only a handful of burials.

Mostly those who are related to one of the existing residents or someone involved in the upkeep of the cemetery.

The work of people like Susan will ensure that they are taken care of as long as there is a Minneapolis.

By the 1870s, cemeteries were once again changing.

The Garden Cemetery movement was spreading from the east coast into America's heartland.

In the garden cemetery, more focus is spent on landscape and design.

The idea is that beauty of a resting place helps heal the pain of death as the living pay their respects.

Lakewood Cemetery in Minneapolis is a great example of this Victorian era cemetery in Minnesota.

To learn more about Lakewood, I had the incredible opportunity to spend an afternoon with long time building and grounds director, Paul Aarstad.

- Everything that you see or we'll see today is my responsibility.

- Well, I'm excited for you to show me the cemetery today and I think it would be appropriate.

Let's start in the old section first, don't you think?

- We're at the oldest or the original section number two, this is where our first burial took place in 1872, over 150 years ago this August.

- This might be my favorite because I love history.

And as I look at these monuments out here, I not only see architecture, landscape, but I see history.

- Oh, this is the place to be.

Section two is really has the movers and shakers of Minneapolis.

Not only from the very rich but also to the very first.

- Paul, how could these early pioneers even afford to build these monuments like this?

- Well, actually they weren't that expensive.

If you think about it, wealth wasn't taxed then back in today and craftsmen were really a dime a dozen.

Think about it.

If you wanted to construct a monument like that, or like this one up here, you'd have to commission an artist.

And then that artist could command a lot of money.

While 1800s, these were plentiful.

They came over from Italy, Europe, and all looking for work, so it was rather cheap.

Each one of these monuments is telling you a story about the person, not only in the monuments but also in the landscape as well.

A cemetery is always changing and it's always evolving.

And as the society changes and evolves, so does a cemetery.

- [Doug] Paul and I continue our timeline walk through the rolling landscape of Lakewood.

- We just came from the section where all the movers and shakers of Minneapolis were with the bigger monuments.

But if we look over into this part, we see something that's different.

The landscape's changed and what you're seeing here, it's the same time period but a different social economic group, the working class.

Their monuments have a lot of the same architectural features that we saw in the other section but they're smaller.

The lots are a little bit smaller and it's more where the working person was being buried.

- So as I walked this part of the cemetery, I might not recognize the names as I would over here?

- No, but this is where likely, you know, my folks, your grandparents would've been buried or great grandparents- - I wouldn't have been over there?

- Well- - You know.

(Doug and Paul laughs) - Doug, you know how we talked about how a cemetery is always changing and evolving.

This is a good spot to kinda show you this in the landscape.

And one of the first things you'll see is lot less monuments and what's happening, we fast forward some 50 years.

And we know this from a couple different ways.

Look at the Olson monument there, notice the lettering, art deco styling.

That's telling us we're somewhere in the 20s or 30s.

In any cemetery, you can see this change in the landscape and by looking at the architecture and the styles will help you date where you're at.

- [Doug] It's a historical timeline.

- Exactly.

Doug, we're at the end of our timeline on the cemetery evolution.

What we have here, if we fast forward another 50 years, we have what's called a lawn crypt plan which was very popular for a while.

What the lawn crypt is basically this area was excavated.

We pre-installed double decker vaults.

So we have one grave, one marker, one vault for two people.

This is very popular.

When I started here some 40 years ago, of the 2100 cases we did a year, 14% were cremation.

Today, we're at 60% cremation.

And what's changed is of the 60% that we cremate, half of those people are now doing nothing with your cremated remains.

What I mean, they go out to grab a certain spot or what.

Our challenge as a cemetery in the next 150 years is try to get people to value memorialization.

We're developing this new prototype up here and it's to provide a number of different new innovative ways to scatter and to memorialize cremated remains.

Our research has shown that as society changes, so does the cemetery.

So we're creating a new green burial space.

We're creating memorials now that have our void of any sort of traditional type memorials.

So when you're standing in this space, you don't know you're in a cemetery, you're in a garden instead.

- So we started in the old section with the large monuments and we end here.

What a great journey through the whole story of the evolution of the cemetery here at Lakewood.

And it's probably the same story all over the country.

- Exactly, I think people need to realize that cemeteries aren't dead.

They're a living place and we want you to be welcomed to come here as a cemetery and to enjoy its history, to enjoy the horticulture.

It doesn't have to be around a funeral.

- So what is the difference between a graveyard and a cemetery?

The term graveyard usually refers to a burial place associated with and run by a church.

The word graveyard is somewhat straightforward.

It is after all a yard filled with graves.

It is interesting to note that the word grave is derived from a proto Germanic word graben, which means to dig.

On the other hand, a cemetery is a place where people are buried that is not associated with a church.

They are many times connected with local governments such as cities and towns.

The word cemetery is a Greek word which means sleeping chamber.

It symbolizes the idea of the dead as sleeping while they move from human to eternal life.

As you travel throughout Minnesota, you will soon realize that we are a state made up of immigrants.

That fact becomes crystal clear as you stop and visit cemeteries.

The immigrant groups live close together.

They work together, worship together, socialize together.

And finally, were buried next to each other.

From the Northern border town of Caribou where Russian immigrants made their home at the turn of the last century to the Welsh communities of Blue Earth County, I enjoyed visiting ethnic cemeteries to get a better sense of the importance of living and dying with those with shared experiences.

(soft upbeat music) What was life like for the early pioneers here in Minnesota?

Sometimes the only clue to that question is what is written on a grave marker in a cemetery.

One of the saddest stones I have come across in my travels is located in a very small rural cemetery in Renville County.

Frozen to death.

For three days in January 1873, a severe snowstorm struck the Midwest taking the lives of hundreds including 70 Minnesotans.

Pioneer life was hard.

That fact becomes clear when looking at the rugged hard Scrabble faces of this German couple in a cemetery in Wright County.

I had chance to meet local historian, Mary Ahrens Wetmore at the Wind, Sweat Beaver Falls Cemetery.

Our meeting made me appreciate even more the life of the early pioneers.

This is your family cemetery, tell me about that.

- Well, we've been here and our farm is just a mile or so from here since 1861.

The Ahrens family came along with the Wetmore family and many of these other people to a very difficult time in history as you know, Minnesota history.

- I noticed a lot of children's graves.

- Yes, yes, and people had lots of children, I suppose, for one reason that they needed somebody to survive then.

But these people had, ancestors, Henry and many had nine children and they buried three of them.

Their 18 year old daughter had a burst appendix.

My grandma was so distraught, she was sure they had buried her alive and so in the dead of winter, in the middle of the night, my grandpa had to bring people over to dig her up and make sure that she did not get buried alive.

- [Doug] This is a special place, isn't it, Mary?

- This is a special place.

- We sometimes think that life on the frontier was short by today's standards but not always.

I was walking through a church cemetery near Norwood Young America and I came across a very unique marker.

Bridget Flood was born in Donecal Ireland in the year 1758.

But what really surprised me was her death date of 1873.

Some of our pioneers did make it well into their golden years, 115 years old, is it possible?

In rural Chippewa County, along a quiet country lane, you will see a small family cemetery tucked into a gro of trees.

The Swensson Farmstead, with its family burial plot is a good example of 19th century pioneer life.

But there's more to the story.

Celeste Suter from the county historical society meets me at all of Swensson's old house.

- Olaf Swensson finished this house in 1903.

This farm was donated to the Chippewa County Historical Society by his son, John Swensson who was the last surviving male heir.

- Olaf was a unique man, wasn't he?

- He was an innovator, he was very forward thinking, had unique ideas about politics and religion and has some interesting artifacts in the basement.

- Let's go inside.

- Are you ready to go see?

- Yeah, let's do it.

- Well, Doug, we're down in the basement now and I would like to show you these unique artifacts.

- What are they?

- Well, these are the forms for the tombstones that we will find out when we go out to the cemetery later.

- [Doug] So he made tombstones down here in the basement?

- He made the forms and he cast the tombstones down here in the basement, yes, indeed.

- For who and how many?

- Well, he made them for his family.

He also built the caskets for all of the family that proceeded him in death, except for Katie.

- And look at the workmanship.

- It's all hand carved, the designs in the tombstone.

The face of the tombstone and the back of the tombstone are just incredible.

He was a very skilled carpenter.

- So these were the forms but what is the material that he used?

Was it concrete?

Was it- - It's, yeah, it's poured concrete.

- Okay.

- And you'll see that one of the stone has been repaired since then.

We have found that the condition of Olaf stone is not quite as good as the other stones.

Maybe John didn't have the secret formula for making a really good concrete but he did the best he could.

And John was tasked with completing Olaf's tombstone markings and if you notice, it says 1921 but Olaf died in 1923.

So the question is, why does it say 1921?

Did Olaf complete his tombstone early so that he would have it ready to go and then didn't die for a couple of years?

Olaf was diagnosed with senility at the end of his life.

So did he just pick a date and go with it?

Did he have a premonition or did John just not have the skills that his father had and thought a one was a lot easier than a backwards three.

- And behind you Celeste, is his work bench.

- [Celeste] Yes.

- [Doug] That's really cool.

- [Celeste] Yep, these would've been some of the tools he would use to make not only the tombstone forms but also the caskets that he made for his family.

- Do you think it was fairly common for folks in rural Minnesota to be buried on their farmstead back in those days?

- [Celeste] There are quite a few rural farmsteads that have cemeteries on them.

Some of them are, you cannot even find anymore, they've just been absorbed by crop land and they might be in a Grove and in disrepair.

- [Doug] Kind of lost?

- Right.

- Right.

- But we're fortunate that we have this one, it's in such good condition.

It's been restored and it's well maintained.

- I'm anxious to go out to the cemetery.

- [Celeste] Okay, let's go.

This is the cemetery where nine of the family members are buried.

- This is amazing Celeste because I got thinking about why Olaf put 1921 on his marker but he didn't die until '23.

My theory is he made his marker in '21.

He put it up here knowing that upon his death, they wouldn't do it the way he wanted it.

So he did it early.

That's why it's his erected 1921 not died in '21.

- [Celeste] That sounds very plausible.

- And you know what Celeste, we do that today.

We buy our cemetery plots.

I know many people that buy their markers in advance, put their names, they'll put their birth date in and they'll leave the death date open to save their family the trouble upon death.

So I think Olaf was thinking about his family.

- The other mystery we have is the mystery of the two Swens.

We have Sven Olaf and Sven Peter who are both sons of Olaf and Ingleberg who passed away at very young ages.

Sven O. passed away at age eight and Sven Peter died at age four.

You'll notice that his stone says Sven O. Swensson as does the other one.

I don't know if maybe Olaf just to use the same form and didn't change the O, we don't know either.

We do know that that the second one was known as Sven Peter.

There are more mysteries that we're uncovering every day and as we start restorations on the house, I'm sure we'll find a few more.

For some people they're so depressing but there's so much joy and hope.

It's just wondering what this person was like.

What was little Sven like when he was running around, was he chasing chickens on the farm?

Or you know, helping with the cows or whatever but just to know that these were people who lived and this is our destination for all of us really.

(soft upbeat music) - All too often, I come across graves of children.

These markers are the most emotional of all.

What was the story?

Was it an accident?

Or one of those many childhood illnesses that made life so hard for the pioneer family?

In Southeast Minnesota, near the town of Houston, I came across a country cemetery marker that emphasizes this fact.

Tucked in the back of the cemetery was a large evergreen tree with a marker at its base.

What really stood out for me was the last sentence on the marker, who were just passing through.

We will never know how many children died on the trails.

And almost for certain, the families were never able to return to take care of the graves of these little ones.

What were the major causes of death for children in the pioneer era?

Typhoid, scarlet fever, diptheria and cholera were the primary causes of death in the years leading up to the 20th century.

In 1918, the Spanish influenza hit hard, not only affecting children but young adults as well.

In Northern Minnesota, near Red Lake Falls, I found one family that lost four boys to the flu in the early winter of 1918, all in a span of one week.

Tragedy didn't always come in the form of childhood diseases.

in Luverne's Maplewood cemetery, we have a very sad story that local historian, Betty Mann shared with me.

In the early hours of January 24th, 1919, a mother tragically took the lives of her five children in order to save them from the threat of the Spanish flu.

The children were shot as they lay asleep in their beds.

After shooting her children, the mother, Clara Hanson, who was pregnant with her sixth child attempted to take her own life.

Clara was sent to an insane asylum in South Dakota and a few months later gave birth to a daughter.

The story takes an interesting turn in 2011 when local folks in Luverne remember seeing an elderly lady all by herself, visiting the graves of the five Hanson children.

Could this have been the last child of Clara?

Walking cemeteries, I always look for our military markers.

Sometimes I will read the names aloud and reach out and touch the stone as a way of remembering.

In most cases, their markers are easy to recognize.

The simple white marble stones that mark the graves of the country's fallen soldiers have changed very little over the decades.

From our three large military cemeteries to the rural country grave yards, you can walk along and read the names and wonder about the lives of these American heroes.

The United States Department of Veteran Affairs furnishes upon request at no charge to the applicant, a government headstone or marker for a grave of any deceased eligible veteran in any cemetery around in the world.

Minnesota has a long honored military history.

In one of the most beautiful landscape cemeteries, Woodlawn in Winona, I met with local museum educator, Jennifer Weaver.

- We have over 100 military graves and then and some ranging from many wars throughout time and we have one in particular here from the revolutionary war of Stephen Taylor.

Taylor is the only known revolutionary war soldier buried in the state of Minnesota.

So we feel pretty special in Winona and at Woodlawn to have somebody of that far back in our history here.

He died about a month after turning 100 out here in Minnesota that he moved with his family later in life, 90-something years old to Minnesota in 1854 as Minnesota was still a territory.

Moved to Winona County, new land, new life and lived to be about a month over 100.

- From Stephen Taylor in Winona to our most recent veterans, our cemeteries are virtual military history lesson.

It is estimated that Minnesota volunteered 25,000 soldiers to the American Civil War in U.S. Dakota conflict.

You will find thousands of these heroes resting in almost any cemetery over 100 years old.

We even have a few Confederate soldiers buried here.

In Duluth, we have the unique honor of having the last surviving member of the Union Army.

Albert Henry Woolson had outlived over 2 million Civil War Union Army comrades when he died Duluth on August 2nd, 1956 at the age of 109.

Woolson was buried with full military honors.

Near the small Hamlet of Beaver Falls in Renville County, I found a Buffalo soldier's grave marker standing sadly all by itself on the edge of the cemetery.

Long time resident, Gene Malecha shared with me what he remembers about this soldier.

- The marker is right here, it's Thomas Boney.

He was a African American that must have came up here years and years ago, probably came up on a rail road.

We would go down to his place, my brother and I would ride our bicycles down there because when we'd go down there, he'd always give us a piece of candy.

He was just a fine gentleman.

He was in the original 25th infantry which was called The Buffalo Soldiers and it was all made up of African American people.

The record of the 25th was very good.

They had very few AWOLs and they were good soldiers and they did a wonderful job.

- There's been a lot of good stories written about The Buffalo Soldiers.

- Yes.

- But I noticed he's buried on the very edge of the cemetery here.

- Well, yeah, that's kind of an interesting part because that was part of racism.

And my dad, well, after he passed away, he found out he was in the military and they had a military funeral and this was his end of the cemetery, just barely.

- We honor him today.

- [Gene] Yes, sir.

- In 1948, President Harry Truman issued an executive order eliminating racial segregation in America's armed forces.

Minnesotans of all backgrounds served in the wars of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In 1917 and '18, Minnesota once again answered the call to serve in the war to end all wars, World War I. I have found and photographed hundreds of these markers, that generation is completely gone except for the memories.

Some call the veterans of World War II, the greatest generation and it's hard to argue that title.

In Luverne, Minnesota, I discovered a rather unique and interesting piece of military history from World War II.

My friend Vance Walgrave, meets me out at the Catholic Cemetery to share the story.

- This is another monument that's very interesting of a local hero from this area.

And we're in St. Catherine Cemetery in Luverne.

And this is a Memorial for Father Sampson who was a paratrooper chaplain, fought in three wars, World War II, Korean War, The Vietnam War.

And in the World War II, he was actually paratrooped behind enemy lines, he was taken captive, was POW for a long time.

And one of his experiences was saving this Private Ryan that had lost his brothers in the war and he was chasing him down.

And the movie "Saving Private Ryan" was fashioned after his story.

- In more recent memory are the men and women who served in Korea, Vietnam, and the war on terrorism.

As I was driving through the city cemetery in Marshall, Minnesota, a gravestone caught my eye.

Now here is one soldier I would've enjoyed talking with.

George Matthews fought in four U.S. wars throughout his military career.

Minnesota is honored to have resting in its cemeteries, 37 congressional medal of honor recipients.

From Duluth to Winona, from the Twin Cities to Fergus Falls.

These heroes should never be forgotten.

When I walk past many faded military markers, some almost unreadable, I think about the forgotten lives of these heroes.

I'm reminded of an old verse I read many years ago, let us now sing the praises of our ancestors in their generations.

All these were honored in their generations and were the pride of their times.

Of others, there is no memory.

They have perished as if they had never existed.

They have become as though they had never been born but their name lives on generation after generation.

What is an epitaph?

According to the dictionary, it is a phrase written in memory of a person who has died.

Something by which a person time or event will be remembered.

Many epitaphs are words of advice or encouragement for us, the living.

Some are just a few short words but others are lengthier, poetic versus.

I find some that are clever and funny.

And others are sad and mournful.

I sometimes enjoy reading them aloud at the grave as if the deceased can actually hear me.

The style and choice of words have evolved over the years.

Today's epitaphs are more visual with images etched into stone.

That gives us a clear picture of what they wanted us to remember them by.

Everything from sports cars, tractors, to the cabin at the lake.

Along with meaningful epitaphs, cemeteries are full of symbolism.

Many of these symbols were popular during the Victorian period but like poetic epitaphs many have been lost to more modern, generic memorials.

Trava Olivier, the Pipestone Museum educator meets me out at her local cemetery to talk symbolism.

- Well, Doug, you asked about symbolism and this cemetery is full of a lot of different symbolism.

But there's a few right here that I'd like to share.

Right behind me is an urn, the urn is the second most popular symbol in a cemetery, the cross being the first, but urns represented immortality and sometimes they were shrouded or draped with some type of a blanket looking object and that was to symbolize the passage or the line between eternal life and physical life on earth.

This one's unique because it has a kepi or a hat on it and the young man that is buried here was a Spanish American war veteran.

Behind that, we have what I call sometimes a modern woodsman stone but it's a tree, it looks like a tree stump, it's been cut off at the top.

The branches been cut off and it was meant to symbolize that life had been cut short by death.

Also over on this side, we have some lambs and lambs that speak near and dear to my heart.

I think it's probably just because I'm female and a mother and no, I've not lost any children but the lambs was a symbol of an infant or toddler or a child's life.

And so, whenever I see a lamb, it always makes me go, what's their story because they didn't live long enough to create their full story or tell their story themselves.

So I wanna know about the time they were we're here with us.

- [Doug] Another interesting piece of history found on memorials are the photographs.

Headstones from centuries ago often contain just names, dates, and sometimes a little phrase or poem.

It's hard to imagine much about the individuals beyond the numbers and the letters.

But when you see a headstone with a porcelain plaque containing a portrait of person or a couple, you can look into their eyes and imagine how they lived, what they valued and the legacy they left.

Although we have lost some of the old style memorials, my visit to the Blue Earth Monument Company helped me understand the future of memorialization.

The company was established in 1877 in Albert Lea and soon after move to Blue Earth making this the oldest monument company in Southern Minnesota.

Lori Maher and her husband Mark, took over the family business in 2008.

Do you work directly with the public or do you work with local funeral directors?

- We work actually with directly with the public.

- [Doug] So they come in into the store here.

- [Lori] They do.

- [Doug] And then you help them make those difficult decisions.

I imagine that is a pretty tough part of the job.

- You know, it is.

And it's also most for us is when they are young kids, when we have to deal with young families.

You know, someone that's lost a young one is probably the hardest part for us.

And we try and make it as easy as possible for people.

We have a great design program, so we can actually design things on the computer so they can see what it's gonna look like and that's very helpful.

We can add artwork and all of those things that somebody wants.

- So you can either sandblast the design, which you could pick any granite color and you can sandblast, it works on anything.

If they don't want it sandblasted, they could do either diamond etch which either we have it on a machine or we have a artist on staff that can do it by hand.

Talking about the etching, the diamond etching that Steve is doing, he's really doing it, it's so personal, you know, for the family so that they can create anything that they want.

Every stone is really custom.

It's all personalized so that everyone is different.

There isn't one the same.

- [Doug] What does it take to maintain a cemetery?

Throughout my travels in Minnesota, most cemeteries I find are well cared for and are the pride of the community.

Due to our changing seasons here in Minnesota, cemeteries require year round care.

I am always encouraged when I see or meet those lucky folks who take great pride in the upkeep of these treasure places.

One of those people is Gretchen Pederson, caretaker at Pioneers & Soldiers Cemetery.

Hi, Gretchen.

- Hello.

- You have the best job in the world.

- I do.

- You love it here, don't you?

- I do.

- Tell me what you do here, actually?

- I'm the caretaker for 23 acres at Pioneers & Soldiers.

I've been working here since the end of March.

- [Doug] So you're new?

- Yep, to here.

- [Doug] Yeah, To here.

- But I worked for the city of Minneapolis for the past seven years in the street division.

And I took care of the roads prior to this, so.

- [Doug] Okay.

- Yeah.

- [Doug] And you take care of- - 23 acres.

- Well, I make the roads here now.

I kind of mow them out and kind of give you the little breakdown of where the cemetery roads are, that's breakdown where the markers are in the cemetery.

- Tell me what is a typical day for you here?

- Typical day is coming in, I open by eight o'clock.

I open the gates, I unlock the gate with the cemetery key that opens all of my locks here in the building.

- Is it a skeleton key?

- No, it isn't.

Won't that be cool though?

- It would.

- Yeah, nope.

- And then?

- And then I pretty much start my day and see what I need to pick up first for debris inside the perimeter and outside the gate.

And then after that, I'd take care of the leaves, if there is any leaves to pick up right now, I'm just gonna blow them to the gate or blow them to the fence line.

And I mow, I weed whack and pick up sticks.

- Do you have a systematic way of, I'm gonna do this section and then move and rotate all the way around?

And eventually when you get back over here, you gotta mow again.

- Yeah, so sometimes if it's like around Memorial Day or you know, any holiday, I'll try to go and get sections taken care of like this but I concentrate up by the carriage house for the events that happen.

- If you were going to mow it all at one time, how long would it take?

- [Gretchen] It depends on weather but I can get it done probably within five days.

And that's mowing straight.

- [Doug] Yeah.

- [Gretchen] Yeah, yeah.

Not weed whacking up to- - [Doug] But I notice you wear headphones.

- I wear ear protection.

- [Doug] Ear protection.

- Yep, I just wear the ear protection- - [Doug] Just the noise of the machine, it just- - Yeah, I sing.

I pretend I can sing.

(laughs) - And you have an audience, don't you?

- Oh, I do.

All the birds, all the- - But no, all the people.

- And the people, my residents, 22,000 residents, I take care of here.

- Don't you love that?

- I do.

- I imagine you have gotten to almost feel like you know some of the people that are resting him.

- Yep, I always say hi to Maud Mabel back there.

Hi, Maud Mabel.

Yeah, there's a really cool marker that's out there that's like a hand.

There's a gentleman, he froze to death after helping someone come back from work and everybody thought he was tipping the bottle or something like that but he actually froze to death walking back to his house.

So it's a hand that's on his grave and I always high five it when I mow by him, it's like, hi there.

This is the best job I've ever had.

I think that this is the job I was supposed to have years ago, but it was waiting for me.

It wasn't the right time yet, so.

- In another life I would've done the same exact thing.

- Hmm.

- Hey, thanks for sharing that with us.

- Yeah, no problem.

I have no regrets, this is the best job ever, like I said.

- It's awesome, high five.

- Thank you, thank you.

- Although Minnesota has a lot of beautiful well-maintained cemeteries, I have run across a few that time has forgotten.

These are sad reminders of how fast our history can be lost.

As I've been traveling around the state of Minnesota, I've seen a lot of cemeteries.

Most of them are well known but I'm back here in the woods near a small town that's been lost to time and the history.

The town was called Vicksburg and a top of hill not far from the main town is a lost cemetery.

They say there's 14 people buried here but my guess, there are more.

I'm standing near this fenced grave marker area here.

As an example, of the people that lived here and the tragedies of being a pioneer here in Minnesota, the Bickel family lost two children, just one more example of the hardships of the pioneers.

I love these lost places tucked back in the woods.

How many more are out there that we don't even know of?

Thankfully, there have been communities that have made an effort to respectfully take care of the dead whose identities are unknown.

- This is the spot we call Potters Field.

It's in the back Northwest corner of the cemetery and it's the historic society's understanding that this was the location where any unknown individuals or the poor and indigent that couldn't afford a funeral were buried.

We're also aware there was an early cemetery in town, kind of on the south west edge and when Woodlawn was started in the mid 1890s, all those graves were reentered here in Woodlawn and the city does not have great records on who's here but it is our understanding and belief that they were put into this section of the cemetery.

- What is the future of our cemeteries?

I feel pretty optimistic after seeing and hearing what communities, cemeteries and individuals are doing today to encourage future generations to see these sacred good places in a positive light.

Cemetery tours are becoming more and more popular these days.

Trava, the Pipestone Museum educator shares her passion for these community outreach events.

So you do tours, are these bus tours, school tours, what kind of tours are they?

- They are walking tours.

We invite citizens to meet us at the cemeteries.

We tell 'em the date and the time and they come out.

There are roughly 18 cemeteries in Pipestone Counties and I've held tours in probably eight of them and the rest of them are on my radar for the next few summers.

We usually start in about April and run through August into September and to do at least one a month.

Do three different kinds, sometimes we talk about the symbols that are on the different stones.

Sometimes we do what we call biography tours, so we're sharing the life stories of individuals buried there and sometimes we do military tours.

So we focus on Civil War veterans or World War I veterans, or pick your era and we plan a tour around them.

- Of all your tours, what is the most popular one?

- I think the biography tours really have been the most popular.

It's sharing the stories of the individuals that are buried there and we go all over the county, so we're finding different people come to each one.

- How do we get the younger generation to come out to cemeteries?

- I think you have to start as a parent by taking them and sharing the family stories.

But there's history in the cemetery if you just go, look at the stones and start asking the questions and finding the answers to 'em.

- The Historical Society in Winona holds a wonderful community event each year at Woodlawn Cemetery.

- I think this is the 23rd year, has been putting on what they call The Voices of the Past Cemetery Walk.

And it really is an incredible event because it teaches so many of our regional students first, to respect death and to understand death but also then to really look at history and the important people that may have come before them.

So it's not just names on a stone.

And so, we get some community folks to volunteer.

They come out in droves and we do it for the school kids during the week and on the weekend, it's for anybody.

- That fight slowed them down just enough for my partner and I to grab 'em, take them back down the hill and arrest them.

- I'm sort of the person who brings the dead to life, so to speak.

Perhaps we should begin at the beginning, yeah?

- Yeah.

- Yeah?

- Yeah.

- Yeah, yeah.

- The official cause of death was a softening of the brain.

These are volunteers, some of them with very little theatrical experience at all.

Some are ringers you know, they come from community theater and they're upset they don't have a song but others are people who don't normally do this.

- Can you imagine?

- Oh my goodness, they were just a bunch of good old boys.

- Well, how do you think this all came to light in the first place?

- This year's theme was a very popular theme from about a decade ago and it was skullduggery and scandals and people who are maybe not quite the ones you would wanna remember from Winona, the ones with a little bit of a dark history.

- And as matter of fact, your husband- - Well, I think once they get over the ooh, what are we doing here in an hooky place, they start to really think of history as something that can come alive for them.

When they hear someone from 1840s start to talk, they sort of go, wow, this is kinda cool.

Somebody should be doing this about me one day, I hope.

And it is quite a lovely spot.

Doesn't just feel like it's dusty and old and mild dewy, it comes alive for a little bit.

- In Waseca's Woodville Cemetery, I had the chance to visit with published author and longtime friend, Rachael Hanel to get her personal cemetery perspective.

This cemetery is special to you, isn't it?

- Yes, it is.

- Why is that?

- Well, it's special for many reasons.

I grew up in Waseca and my dad was a grave digger.

So this being the largest cemetery in the Waseca area, I spent a lot of time here as my dad did his job.

And he and my mom also mowed and maintained cemeteries so long summer days is where I was with them.

They just brought me along as they worked but it's also a special cemetery for me.

My dad passed away when I was 15, he was 46 and he's buried here.

So we have the gravestone here for my dad and my mom.

- [Doug] Rachael took me to another favorite marker of hers.

- Well, Doug, this is one of the favorite gravestones here in Woodville Cemetery.

I came across this stone, I was very small.

I was, you know, five or six years old.

And as you notice at the top, there's kind of this clasp.

And if you are a young child, you might have a curious mind and wonder what's on underneath that.

So I would come by and I would just flip this up and there is a photograph underneath it.

And this is Vicky Middlestead.

I didn't know her, I didn't know anything about her, I didn't know her family but here's this picture of her.

And I was just captivated.

It's such a beautiful photograph.

If I think she's just so beautiful and even all these years later, I still do think it's just a beautiful photograph.

And this would've been the first instance that I saw of somebody who was not that much older than me at the time.

I really had to try to reconcile the fact that here was somebody who looks so vibrant and young and beautiful with the fact that he had died.

So that really was my first moment that I confronted this idea of mortality and that we all are gonna die.

- But do you still visit cemeteries today?

- I love visiting cemeteries.

I especially love it when I travel to go to cemeteries that I have not been to before.

And every time I go to a new cemetery, there's something in there that jumps out.

There's a story that speaks to me and I just love finding those hidden stories that are in cemeteries.

- Should we all visit cemeteries?

- I think absolutely, we should visit cemeteries.

Cemeteries were made for people to visit.

For one thing, they beautiful.

There's nature, there's trees, there's birds, there's flowers, they're very peaceful.

But I think another important reason to visit cemeteries is that they are a community.

Look all around here, there's people here.

They are a community just like you and I are part of a community.

- I like what you said.

A cemetery is full of stories yet to be explored and enjoyed.

- [Rachael] Yes- - And not just about funerals.

- Not at all and I think when people come to cemeteries, if they take some time and they walk around and they look at gravestones, if you just settle down and let that quiet come over you, those stories will start to speak to you too.

It's our connection to the past.

- As a photographer and historian for the past 30 plus years, I have crisscrossed this great state of Minnesota, oftentimes style at our mini cemeteries.

These stops are sometimes only for a few minutes but are a nice break.

Walking these grounds gives me a chance to reflect and take stock in what is important in life.

On one level, cemeteries are about the past we bury in them but on another, they are inherently future oriented.

Memorials are nothing if not directed at those who will look upon them and be called to remember.

Whether we embrace or deny it, death remains a central fact of life.

Cemeteries are a symbol of our humanity, of our intelligence and a reminder of the brevity and the preciousness of our time on earth.

(soft upbeat music)

LANDMARKS: Cemeteries of Minnesota

Travel along with MN historian Doug Ohman and explore the fascinating world of Cemeteries. (32s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

LANDMARKS is a local public television program presented by Pioneer PBS

This program is made possible by contributions from the voters of Minnesota through a legislative appropriation from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and viewers like you.