Prairie Yard & Garden

Marla Spivak and the Health of Bees

Season 38 Episode 2 | 28m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

Marla Spivak is renowned as one of the most knowledgeable bee researchers in the United States.

Marla Spivak is renowned as one of the most knowledgeable bee researchers in the United States. Her work at the Bee Lab and Bee Squad at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, along with her coworkers, provides a fascinating glimpse into the world of bees and the plants they thrive on.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Prairie Yard & Garden is a local public television program presented by Pioneer PBS

Production sponsorship is provided by ACIRA, Heartland Motor Company, Shalom Hill Farm, Friends of Prairie Yard & Garden, Minnesota Grown and viewers like you.

Prairie Yard & Garden

Marla Spivak and the Health of Bees

Season 38 Episode 2 | 28m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

Marla Spivak is renowned as one of the most knowledgeable bee researchers in the United States. Her work at the Bee Lab and Bee Squad at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, along with her coworkers, provides a fascinating glimpse into the world of bees and the plants they thrive on.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Prairie Yard & Garden

Prairie Yard & Garden is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

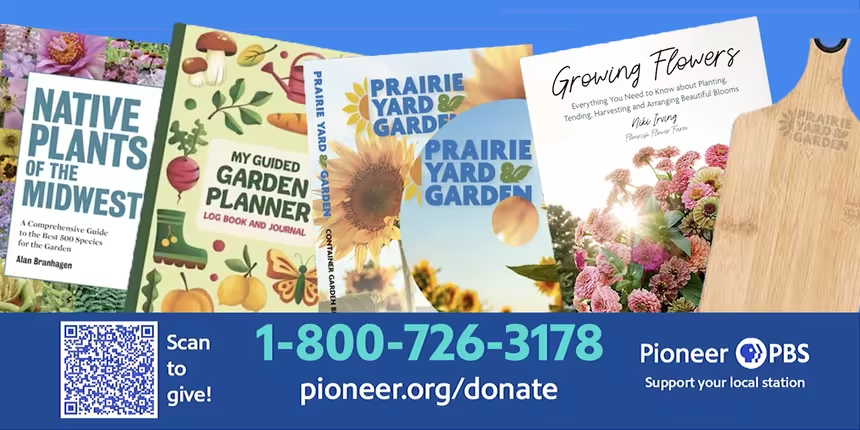

Prairie Yard & Garden Premium Gifts

Do you love gardening? Consider becoming a friend of Prairie Yard & Garden to support this show and receive gifts with your contribution. Visit the link below to do so or visit pioneer.org/donate.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(bright music) - Years ago we did a "Prairie Yard and Garden" show at Old Mill Honey Farm near Barrett, Minnesota.

It was so interesting and fun for me, though I'm not so sure the camera guys enjoyed it as much as I did.

We were all wearing bee suits and they were running the cameras on a good hot summer day, so honey was not the only thing dripping that day.

I learned about the University of Minnesota Bee Lab and have wanted to visit ever since.

Well, come along with me as we explore and learn more.

- [Announcer] Funding for "Prairie Yard and Garden" is provided by Heartland Motor Company.

Providing service to Minnesota and the Dakotas for over 30 years.

In the heart of truck country, Heartland Motor Company.

We have your best interest at heart.

Farmers Mutual Telephone Company and Federated Telephone Cooperative.

Proud to be powering Acira.

Pioneers in bringing state-of-the-art technology to our rural communities.

Mark and Margaret Yael Jolene in honor of Shalom Hill Farm, a non-profit rural education retreat center in a beautiful prairie setting near Windham, Minnesota.

And by Friends of "Prairie Yard and Garden."

A community of supporters like you who engage in the long-term growth of the series.

To become a friend of "Prairie Yard and Garden," visit pioneer.org/pyg.

(bright music) - I have wanted to visit the University of Minnesota Bee Lab for a long time.

The Bee Lab's mission is to promote the health, diversity and conservation of bee pollinators through research, education and mentorship.

I have heard so many good things about Marla Spivak and her work with the Bee Lab.

I'm not sure if she would be the queen bee of the lab or the worker bee as she has done so much good work.

So thanks for letting us come to visit.

- Thanks for having me.

How fun.

- Well, what is your background?

- My background?

Let's see.

Well, I was not interested in bees as a kid or insects at all.

I became interested in honeybees when I was in college when I was about 18 years old.

And then I went to work for a beekeeper and then I was hooked.

They hired me as the professor of honeybee research.

It's a long tradition here at the University of Minnesota.

There's over a hundred years of bee research at the University of Minnesota here, and I'm one in a long line of professors.

- Marla, how did the Bee research program get started?

- Well, they began in 1913 with Father Francis Jager.

And he started St. Boniface's Church.

He immigrated from Europe.

And he also was the bee professor.

And he stayed here until about the mid-'30s, and then they hired another professor, Maurice Tankery, and then Dr. Hedak from Ukraine, and then Dr. Fergala from Canada.

And then after him, I was hired in '92.

So there's been a series of professors before me.

- Well then, when was the Bee Lab actually started?

- Well, we always had a lab.

There was always a lab space in the Department of Entomology where I'm housed, but the honey extracting and other things were done in a little facility behind what's now the Bell Museum of Natural History of the university.

And in 2015, we were able to get funding from the state to build this new facility.

And they demolished that old cinder block building and we got this wonderful lab.

- So what were all the different groups or organizations that helped and contributed to getting this lab built?

- Right.

I attribute a lot of it to the Bee Squad, which is a program that I started here within the Bee Lab.

The Bee Squad interfaces with the public.

They're the outreach arm of our research and education lab.

They really have an amazing reputation with the public.

The public really knows about them and all of the educational programming that they do.

And because of that, we started to accumulate a donor base.

And when the university received permission to build a new building, the state said they would pay for two thirds, and we were tasked with raising the other third.

And through all the goodwill of our donors and people we reach through the Bee Lab, they donated that 2.4 million to help get this lab built.

- So how many people are part of the Bee Squad now?

- Well, there's at least a dozen.

There's six full-time and then a bunch of other part-time and summer help.

And then that's separate from the bee research arm that we have.

So it's honeybee research and also inside is another professor, Dr. Dan Cariveau, and he researches native bees.

He's a native bee ecologist.

- [Mary] So how many hives do you work with now?

- [Marla] Well, Bee Squad has over 200 and we have 150 or so.

So, together, there's probably around 400.

- [Mary] What kind of research are you working on now?

- [Marla] Well, my whole career has been spent doing research on what we call social immunity, which is how honeybees keep themselves healthy.

What their healthcare system is, basically.

So honeybees live in a very densely populated colony, thousands of individuals.

And how do they prevent disease transmission?

What behaviors and strategies do they use to keep themselves healthy?

- [Mary] I've heard that there is a mite that really affects bee health.

Can you tell us about that?

- [Marla] Right.

A mite is like a little tick and it sucks on the bee's hemolymph, their blood, but also their fat body tissue.

It's an important organ in their bodies.

It moves around.

Unlike a tick, it can feed for a while and then move to another bee and it transmits viruses.

It reproduces...

This mite reproduces on the developing brood, the baby bees.

It's called Varroa destructor.

It has a great scientific name.

It's very destructive.

And between the damage the mite can do to weaken the bees and the viruses it transmits as it's feeding on bees, it's devastating to bee colonies.

So they were inadvertently introduced in the United States in the late '80s.

So they've been here for quite a while.

There are some organic insecticides, formic acid, oxalic acids, some lighter compounds that we can use to control the mites, but they're very difficult to control.

One thing that I've been doing the whole time I've been here is breeding bees that can resist these mites on their own.

- [Mary] What are some of the other research projects that you're working on?

- [Marla] Well, the main theme is social immunity or how honeybee colonies keep themselves healthy.

And one of the ways they do that is called hygienic behavior.

It's a genetic trait, and colonies that have this genetic trait are able to sniff out baby bees that are sick and they sacrifice them.

They toss them out the front door.

But bees are able to sacrifice a few for the good of the colony.

That's how they operate.

We are trying to figure out, for example, if bees are detecting the baby bees that have a virus and they remove it.

Do they end up spreading the virus or are they curtailing the spread of the virus?

- So, especially in the spring of the year, do you have to feed the bees?

- We try not to.

There are some years where we do, but, generally, we leave enough honey on 'em in the winter where they're fine for the entire winter and into the spring.

So I'm really interested in colonies that are able to survive on their own with minimum human intervention.

I garden the same way with my native plants, by the way.

I just prefer to do as little as I can.

- [Mary] Well, that was one of my questions, is I was gonna ask you, what do you do with the hives in the winter time?

- [Marla] Right.

Well, they stay right here.

So a lot of these boxes are just full of honey that we will remove, and we leave about a hundred pounds of honey on the colonies for the winter.

And they'll work their way through that food all winter long.

And then right here, we cover 'em with a black covering just to absorb some heat if it's sunny out at all, and they survive just fine sitting out here.

Well, they cluster together in a great big group and they shiver their muscles and they generate heat.

So if it's 20 below, it's 60, 70 degrees in their cluster.

- So when they go back out in the spring, how do they tell each other where the food is?

- Right.

So there's scout bees that go find it, you know, the explorers and they find a big patch of flowers somewhere.

The first of bloom is maple, the pollen coming from maple trees.

They produce a lot of pollen and the bees are hungry for protein at that early spring.

So the scout bees go out and they find it.

They'll come back and they'll do a little waggle dance, and that informs their followers of that dance where those trees are, and those followers will go out and find it.

That dance conveys distance and direction.

It's quite remarkable.

- What are the most important issues facing our honeybees today?

- Right.

When you say bees, I'm assuming you're talking about all of our bees.

We have 20,000 species of bees in the world, at least, and honeybees are just one of those, one of 20,000 kinds of bees.

Most of our bees are solitary.

A few are social, like the bumblebees, but the main issues for all of the bees in general, they all need more flowers.

So more nectar and pollen for their nutrition.

They need fewer pesticides.

So insecticides can directly kill them.

Not always.

Fungicides we're learning can have effects on their gut microbiomes.

And herbicides can kill the flowering plants that they need to survive on.

They have their own diseases.

Honeybees have these mites and viruses, bumblebees, solitary bees, they have their own, you know, diseases.

But mostly what they all need, how everybody can really help all of our bees is to be a gardener to plant flowers that they like.

And how do you find the flowers they like?

You just go to a nursery or walk around and you say, "Well, that flower has a lot of bees on it.

What's that one?"

And plant it.

- So can we visit with some of your colleagues too about the plants and more information?

- I would love for you to visit my colleagues.

They have so much knowledge about our native bees and the plants much more than I do.

So, that would be super fun.

(bright music) - Hi, Mary.

My name is Thea Evans, and I'm the pollinator garden coordinator at the Bee Lab here at the University of Minnesota.

And my job is to manage the maintenance of the pollinator garden and make sure that we're doing everything that we can to provide the best habitat for bees, both for their health and for their diversity.

This garden was planted in 2016.

So right after this building was built.

I probably spend four or five hours a week in here weeding.

We have weeds like thistles and I weed those out.

I spend a certain amount of time trimming back plants from the edges where they tend to like wanna flop over into the pathways.

And then we also have a natural areas gardener who works with the land care.

And I coordinate with him.

He'll come through and do things like weed whack around the shrubs and mow the lawn areas.

So we kind of work together to make sure that everything is doing well.

- Do you have both native and non-native plants in this planting?

So this is a native plant garden, and all of the plants that are in here are plants that are native to Minnesota.

And we have those because it provides the best habitat for the native bees of Minnesota.

We have about 500 species of bees that live here in Minnesota best adapted to the native plants that they've evolved with here.

I think it's over a hundred different species of native plants that grow here in this garden.

- [Marla] Do the bees have a preference for, like, single flowers versus double flowers?

- [Yeah, that's a great question.

Double flowers have been bred to have all those kind of extra petals.

They look, you know, really beautiful to us, but often, those extra petals are actually the reproductive parts of the plant that have been bred to be petals instead.

They often don't produce any nectar or pollen.

And so they don't really provide anything for the bees at all.

That's another reason to choose native plants or plants that haven't been highly bred like that, that will still be providing the food that the bees need to eat.

- [Mary] Well, here in the city.

How do the bees find food?

- [Marla] There are many places and ways that bees find food.

So, many trees, actually.

Trees and shrubs provide food for bees, especially in the springtime when aren't a lot of other plants blooming.

All those, you know, the boulevard trees and the trees in people's yards can often provide a lot of resources for bees.

And then lots of people have gardens in their yards.

So if you're walking around in your neighborhood or if you look in your own yard, you may just sort of notice which plants seem to be attracting bees to them.

And then also, a lot of people here in the city are choosing to not use herbicides on their lawn and let some of the flowering plants that grow in lawns actually bloom.

So plants like clover, dandelions, there are a whole bunch of different little plants that will grow in the lawns, and those also provide food for bees.

- [Mary] Thea, what do you do with this in the fall?

- [Marla] So in the fall, we really just let all of these plants stay standing in the fall and over the winter and the seeds from the flowers provide food for birds, it provides overwintering habitat for bees and other insects.

And so we just let it kind of be tall in the wintertime, and then in the spring kind of before a lot of plants start to grow, we'll cut back everything to, you know, between eight and 18 inches and we'll leave those cut stems from the previous year to be nesting habitat for bees that will actually nest in those plant stems.

- Would you be willing to show me some of the beautiful plants blooming here that are great for the bees?

Yes, I'd love to.

(bright music) Let's go take a look.

So this is a rain garden that we've planted to catch water off of this building.

And when it's raining, the water really comes fast off of this building.

And so in this depression in the land here, we've planted a bunch of plants that will do well with that kind of intermittent flooding and then drying out between rains.

And I'm so glad that you're here while the wild bee bomb is blooming, this is one of my favorite plants, and the bees absolutely love it, especially bumblebees.

And it's a really important plant for bumblebees.

It's actually been shown to have immune enhancing properties and helps them fight off diseases.

Another plant that we have in this area is Culver's root that's blooming now.

These are the midsummer blooming plants.

It's a really cool plant 'cause it'll do well in a lot of different conditions.

So you can actually plant this in part shade, but it also does well in full sun.

Has these really cool spires of white flowers.

Bumblebees actually really love this one as well, but we also see a lot of honeybees on them.

You can see some honeybees.

- Thea, there's lots of things blooming here, but you've got grasses too.

- Yeah, so grasses are also important for pollinators.

They're wind pollinated plants, so they don't...

Bees don't visit them for pollen or nectar, but they provide habitat for the bees in other ways.

So they grow really well with the other prairie plants that we have planted in here because they're bunch grasses, they kind of provide a place where bees that nest in the ground can access the soil surface around them.

So they help to provide nesting habitat for bees, which is also really important for their protection and conservation.

We also have this tall plant right here.

This is a really cool plant.

It's kind of a lesser known garden plant.

This is called late flowering figwort.

And there's also an early flowering figwort which blooms in June.

We have some of that in the garden as well.

The flowers are not very conspicuous, they're pretty small, but they produce a ton of nectar and the bees really love them.

Over here we have Virginia Mountain mint.

This one is one that honeybees absolutely adore.

It's in the mint family.

So kind of similar to (indistinct) which is also in the mint family.

It has some of those immune enhancing properties for bees.

- [Mary] We are in the summer and you have beautiful plants, but what about some for the other seasons?

Yeah, so it's so important for pollinators to have plants that are blooming at all times of the growing season.

So starting in the very early spring and going all through the summer and into the fall.

And we have lots of plants that bloom here in the spring.

Trees and shrubs can be really important for pollinators in the early spring.

So we have trees like red maple, we have shrubs like prairie willow, which is one of the very first things to bloom.

And you'll just see that covered with honeybees when that's blooming.

And then there's a plant called Golden Alexander's, which we have in the front of the garden.

And it's a prairie plant.

It's, you know, sort of a medium height plant.

It has yellow flowers as it's in the carrot family and it attracts so many different kinds of bees.

It's one that researchers have found attracts the most species of bees to it.

So when it's blooming, it blooms in the late spring and kind of in that bridge season going from spring to summer when there aren't a lot of other plants blooming often.

So it's a really important plant for pollinators.

We also have some areas in the garden where we have prairie smoke planted.

That's another very low growing prairie plant that blooms first thing in the spring.

And that one is pollinated by bumblebees, actually.

So queen bumblebees, when they're coming out of hibernation, they'll visit the the prairie smoke plants and they use buzz pollination to pollinate it.

And then in fall, the kind of backbone, I would say, of the native plant garden in the fall are asters and golden rods.

We have numerous kinds of asters that grow in this garden.

New England Astor is one of them, which is just gorgeous in the fall that you get those beautiful dark purple flowers.

But we also have at least four or five other species of asters that grow in the garden as well.

And then we have a bunch of different types of golden rods also.

So another way that we provide nesting habitat for bees in this garden is by planting plants that leaf cutter bees will use to cut, they'll cut pieces of leaves out of certain plants and use them to line the inside of their nests.

So we have a sculpture in the garden that's, it's a stone sculpture and it has holes drilled in it.

And the bees nest in those holes and they cut the leaves of the plants, the roses and there's some low bush honeysuckle that they really seem to like the leaves of.

They'll cut little pieces out of those leaves and use them to line the inside of the nests in those holes.

So it's just really important to have that full coverage of flowers blooming throughout the season here in the garden.

- Thanks so much for sharing your beautiful gardens and plants, and for the great information.

- You're welcome.

It's been a pleasure.

(bright music) - I have a question.

My space gets limited sun.

Are there any vegetables I can grow?

- That's a great question.

Here at the Farm at the Arb, we actually have a demonstration of three different raised beds that are almost completely in the shade.

So there's no direct sunlight in the bed I'm currently sitting on.

We are growing right now some carrots right here.

We're going to sow some lettuce seeds and then we also have some bok choy.

These have done really well.

They've all been direct seeded.

On some of the other beds, we've had success growing beets, lettuce, swiss chard, we had water crests.

We've been growing green onions in each one of the beds.

There's so many options that are beyond just lettuce for you to grow and be successful in the shade.

So in these beds, not only are they in full shade, we've also been succession planting, which just means when one crop is done, we immediately reseed it with a new one.

So that's why we're gonna put lettuce here.

We had just pulled out this morning some peas that we grew for pea shoots.

So just to have little stems, but they actually, we let them go and they formed full pods and they were absolutely delicious.

So these are in a raised bed, but you do not necessarily need to grow in a raised bed.

So just remember, if you have shade, you can still grow great food.

- [Announcer] Ask the Arboretum Experts has been brought to you by the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum in Chaska dedicated to welcoming, informing, and inspiring all throughout standing displays, protected natural areas, horticultural research and education.

- My name is Elaine Evans.

I am an extension educator and researcher here at the University of Minnesota Bee Lab.

And my work focuses on native bee and other pollinator conservation and education.

- What kind of research projects happen here and what are your projects here?

- At the University of Minnesota Bee Lab here, we have this fairly unique position where we have two different main branches of research here.

So we have one professor, Marla Spivak, who focuses on honeybee health.

And we have another professor, they're both based in the entomology department here.

He focuses on native pollinator habitat restoration and restoring native bees, documenting native bees.

And his name is Dan Cariveau.

And then we have, both of those labs have extension educators.

So I do outreach and education for the native bees.

There is another extension educator, Katie Lee, who does outreach for the honeybees.

- [Mary] Elaine, why are native bees so important?

- [Elaine] Native bees really fill in really important roles in the ecosystem.

So honeybees are our one kind of bee.

They have certain plants that they pollinate.

They are used in a lot of agricultural crops.

When we're looking at the native systems, wild systems, there are all these other pollinators, 20,000 different species of bees in the world that some have very unique relationships with different plants.

There's some plants that are completely dependent on particular bees to pollinate them.

So by supporting the diversity of native pollinators, we're able to support that diversity of plants.

And then those diversity of plants, they are helping to filter water, they're helping to, you know, grow down deep roots and help with climate.

They're also providing food for countless other creatures that are feeding on those plants.

- Do you do outreach with people in groups in the state?

- I do.

A lot of my research is actually involving the public.

So I do a lot of work with public participation.

So we do bumblebee surveys across the state.

So we have individuals that adopt a grid and they're responsible to go and document the bumblebees that are there and that's helping us as researchers.

We can't get everywhere across the state.

But with the help of these volunteers, we're able to learn about bumblebees all across the state.

In addition to volunteers helping us with research, we also have volunteers helping us with education.

We know that people broadly are aware of pollinators, but they don't often know what to do to help.

So we have a toolkit and training programs to help individuals educate people in their communities about the action steps that they can take to help pollinators.

- If people want to try to help the pollinators, what are some of the steps you recommend?

- We have four action steps that we recommend.

So the first is to plant flowers, and part of that is keeping those flowers free of pesticides so that they can support the pollinators.

We also encourage people to provide homes for pollinators.

So there are bees that nest in the ground, they need undisturbed habitat.

There are bees that nest in stems.

Leaving stems in the garden helps them.

We also want to leave flowers for caterpillars that forage on all kinds of different plants.

So having a diversity of native plants helps those important pollinators.

The third action is climate action.

We know that pollinators are impacted by climate, supporting strong regulations, planting native plants that will have deep root systems, switching to a plant-based diet when you can.

All of those things can help make the climate more suitable for the pollinators and for us in the future.

And we also encourage people to collect data.

So joining one of the programs, so we have programs here at the University of Minnesota.

There's also programs for monitoring monarchs, all kinds of great programs where you can join to help collect data.

Just taking photos of anything that you see visiting flowers and sharing it with the biodiversity portal like iNaturalist is something that helps researchers know where pollinators are to gauge how they're doing.

- Well, this has been just awesome.

Thanks for visiting with us.

- Oh, my pleasure.

- [Announcer] Funding for "Prairie Yard and Garden" is provided by Heartland Motor Company.

Providing service to Minnesota and the Dakotas for over 30 years.

In the heart of Truck country, Heartland Motor Company.

We have your best interest at heart.

Farmers Mutual Telephone Company and Federated Telephone Cooperative.

Proud to be powering Acira.

Pioneers in bringing state-of-the-art technology to our rural communities.

Mark and Margaret Yael Jolene in honor of Shalom Hill Farm, a non-profit rural education retreat center in a beautiful prairie setting near Windham, Minnesota.

And by friends of "Prairie Yard and Garden."

A community of supporters like you who engage in the long-term growth of the series.

To become a friend of "Prairie Yard and Garden," visit pioneer.org/pyg.

(bright music)

Marla Spivak and the Health of Bees

Preview: S38 Ep2 | 30s | Marla Spivak is renowned as one of the most knowledgeable bee researchers in the United States. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Home and How To

Hit the road in a classic car for a tour through Great Britain with two antiques experts.

Support for PBS provided by:

Prairie Yard & Garden is a local public television program presented by Pioneer PBS

Production sponsorship is provided by ACIRA, Heartland Motor Company, Shalom Hill Farm, Friends of Prairie Yard & Garden, Minnesota Grown and viewers like you.