Prairie Yard & Garden

Growing Apples in a Big Way

Season 38 Episode 11 | 28m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

Country Blossom Farm near Alexandria, Minn. is a popular destination that produces fine apples.

Country Blossom Farm near Alexandria, Minn. is a popular destination that draws thousands of visitors each year. Visitors have the opportunity to witness how the farm produces the finest apples, enjoyed for their fresh and juicy flavor as well as their use in creating delicious pies and other delectable products.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Prairie Yard & Garden is a local public television program presented by Pioneer PBS

Production sponsorship is provided by Shalom Hill Farm, Heartland Motor Company, North Dakota State University, Friends of Prairie Yard & Garden, and viewers like you.

Prairie Yard & Garden

Growing Apples in a Big Way

Season 38 Episode 11 | 28m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

Country Blossom Farm near Alexandria, Minn. is a popular destination that draws thousands of visitors each year. Visitors have the opportunity to witness how the farm produces the finest apples, enjoyed for their fresh and juicy flavor as well as their use in creating delicious pies and other delectable products.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Prairie Yard & Garden

Prairie Yard & Garden is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

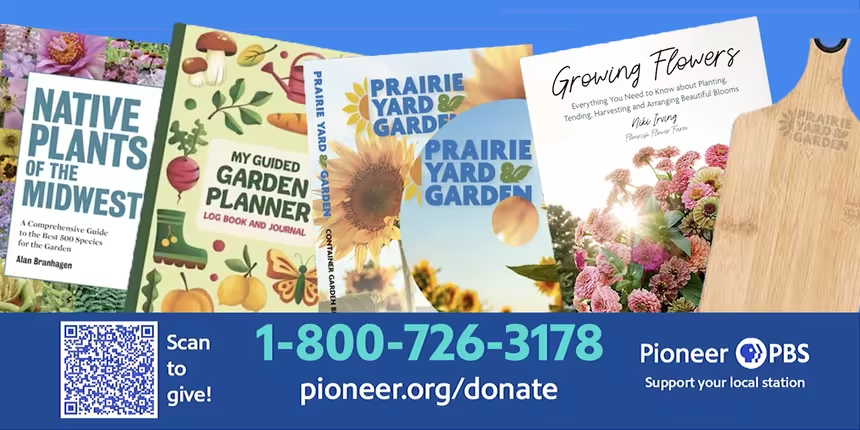

Prairie Yard & Garden Premium Gifts

Do you love gardening? Consider becoming a friend of Prairie Yard & Garden to support this show and receive gifts with your contribution. Visit the link below to do so or visit pioneer.org/donate.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(bright music) - When we have (upbeat country music) extended family gatherings, the talk soon turns to plants.

Well, imagine that.

There are often questions on growing apples, which we also get asked by friends around town too.

Well, I figured if our family members and friends have apple questions, there are probably many of our viewers with those same questions.

So I decided to find someone who has an apple orchard and grows lots and lots of great apples.

We'll get good advice so our family, friends, and viewers can grow great apples too.

- [Announcer] Funding for Prairie Yard & Garden is provided by Heartland Motor Company, providing service to Minnesota and the Dakotas for over 30 years.

In the heart of truck country, Heartland Motor Company, we have your best interests at heart.

Farmers Mutual Telephone Company and Federated Telephone Cooperative, proud to be powering Acira, pioneers in bringing state-of-the-art technology to our rural communities.

Mark and Margaret Yackel-Juleen, in honor of Shalom Hill Farm, a non-profit rural education retreat center in a beautiful prairie setting near Wyndham, Minnesota.

And by Friends of Prairie Yard & Garden, a community of supporters like you, who engage in the long-term growth of the series.

To become a Friend of Prairie Yard & Garden, visit www.pioneer.org/pyg.

(cheerful music) (cheerful music continues) (cheerful music continues) - Apples and fall just seem to go together.

We all think of back to school and apples for the teacher.

There are so many wonderful uses for apples, ranging from eating a fresh crunchy apple to enjoying a cup of hot steamy cider on a cool fall day.

Country Blossom Farm, near Alexandria, produces great fresh apples along with many other products.

I called Troy, the owner, and asked if we could come and get a lesson on growing good apples.

And he said, "Sure."

Thanks for letting us come.

- Well, welcome to the farm.

Glad you're here.

- How did Country Blossom Farm come about?

- Well, so I was working in the IT industry, I did for 25 years, and I'm an outdoors person, I wanted to be outside.

I didn't want to be 60-years-old, staring at a computer screen.

I enjoyed what I did, but it wasn't my dream, I guess.

So we threw around some ideas, orchard was one of 'em, it's something I always wanted to do.

Didn't know how to grow apples to this scale or anything, so we joined the Minnesota Apple Growers Association.

Met with a lot of great people there before we did anything.

So we started looking around the Alexandria area, 'cause there's not really much here, (vehicle rumbling) and we decided we'd pick this farm here.

So we bought this farm in 2009 and started planting apple trees in 2010.

Today, we're at about 11,000 trees.

- [Mary] What variety or varieties did you start with?

- [Troy] Our first planting was fireside, which is an older variety, it's one of my favorites, that's why I planted 'em, 'cause it's so good.

Honey Crisp, Zestar, and Sweet Tango.

Those were our first four varieties that we planted.

- How long did it take for you to get your first crop of apples?

- I think I left a few on the second year, I shouldn't have, but I was excited, and it's hard to take 'em all off.

So, ideally, the third year is when you'll see some crop on 'em, but even in that third year, you wanna limit that crop.

You want that tree to really develop and get its root system going before you start putting apples on it.

What happens if you put the apples on when they're too young?

You don't get growth.

It puts all the energy into the apple, and you can actually runt 'em out, meaning they won't really get to their full size they should because they just get into that fruiting mode, and that's what they do.

So with apples, you need two different varieties for pollination to occur.

If I had all these trees as honey crisps, I'd probably get some apples from outside pollen coming in, but it wouldn't be ideal.

So we kind of spread 'em out so we have different varieties around all the trees, so we're getting pollen and good pollination throughout the orchard.

- [Mary] Do you find that your trees are somewhat cyclical?

Like I heard that, you know, some years they're a heavy producer, and the next year they rest.

Do you find that?

- [Troy] Yeah, so what you're talking about there is biennial bearing.

Certain varieties are more prone to it than others.

For instance, Sweet Tango, like these trees here, they're not prone to it.

I can load 'em up every year, and they'll come right back the next year, and they'll fill the trees.

Same with Zestar.

Honey Crisp, on the other hand, is very biennial bearing.

If they have a heavy crop one year, next year, they won't have any fruit at all, or little fruit.

And what we do to try to avoid that, or keep it at a minimum, is we chemically thin our trees.

So once the fruit is set, and the fruit's about 8 to 12 millimeters in size, we'll go out and we'll assess the fruit load.

How much fruit's on the tree?

Was pollination good?

Was it bad?

Do we need to thin?

At that point, when they're about 8 to 12 millimeters in size, we'll apply a chemical thinner to the trees, and typically it takes about a week, and you'll see a lot of the fruitlets drop.

We do that for several reasons.

Number one is to break that biennial bearing cycle.

The trees decide what they're doing next year about probably, you know, 30 to 40 days after bloom.

So these trees already know what they're doing next year at this point.

If you don't get that fruit off before it makes that decision, then you're not gonna have any effect on your return bloom.

So, with hand thinning, they're just too small to make any difference, and you couldn't get through your whole orchard in time.

So chemical thinning really does that.

- [Mary] Troy, how many trees do you plant each year additionally or replace?

- [Troy] That is gonna vary greatly year to year.

You know, this year I believe we planted around, I mean, if I had to come up with a number, probably around 700 a year we plant, that being a new planting and replacements as well.

So all of our trees, they arrive, they're bare root.

We can usually get about 500 done a day, easily.

- [Mary] Then do you mulch the newly planted trees?

- [Troy] We do not mulch the newly planted trees.

You know, ground cover is a very important part of the orchard.

Problem with mulch is, I have 11,000 trees, and trying to get enough mulch and doing it, it would be a lot of work, it would be very cost-prohibitive.

The other problem with mulch is the vermin like to live in the mulch, so then you have that issue.

We prefer just clean under the trees, it keeps the mice out, all the nutrients go right to the tree, the water goes right to the tree.

In a wet year it wouldn't make much of a difference, but like the last few years have been dry, so when I'm using my well and watering the trees, I want it to get to the tree.

And if it's dry, I'll water 'em about once a week.

And so I can basically flip a switch and water this entire side of the orchard at one time.

- Do you fertilize?

And how do you fertilize?

- We do.

We do fertilize.

With apple trees, they don't require a lot of nutrients.

We apply our fertilizer right after bloom.

That's when the trees are growing, the apples are growing, that's when that really needs the nutrients.

What we'll do is we'll put a granular down in the rows, I have a special spreader that shoots out each side right in the row.

We'll do soil testing to kind of see where all the nutrient levels are in there and stuff as well.

The other thing we'll do is a lot of micronutrients.

And those, we put in with our spray.

So like when we're spraying the trees for fungicide early spring, then we'll have, you know, magnesium, you know, all the different micros, depending on what growth stage it's at.

Like right before bloom, boron's important for fruit set.

So we'll spray that on.

After fruit is set, then we'll spray calcium.

'Cause as that fruit is developing, you need calcium for that cell walls, and for pressure.

And so we spray calcium about every week.

- Okay.

Here's the problem everybody has.

(Troy laughing) What about critters?

- Critters.

Oh boy, which ones?

(Mary laughing) So, you know, the first critter we took a care of was deer.

So we decided early on that we wanted to fence our orchards.

Birds are another one.

Typically, it's crows that we have to deal with there.

So we have bird-scaring devices that we have around the orchard, and that seems to really work.

Especially we have these kites with a hawk that kind of swings around, that really works on the crows.

The little birds, I don't really worry about them, they don't eat too much, but you'll see some apples that are pecked here and there.

Other pests, insects.

So we do a lot of things to protect the trees from insects.

We have a weather station on our farm here that takes all of our weather data, and it goes to a website at Cornell University called NUA.

And it's a public site, anyone can go on it.

So I'll go in, I'll see my orchard, I click on it, and I click apples, then I click pests, and it'll show me all the different insects.

And with the weather data and modeling, it kind of tells you where they're at in their life cycle, so when you can expect to spray.

So it's a tool we use to determine when we're spraying.

In addition to that, we also have pheromone traps in the orchard.

So like for instance, coddling moth, that's one we really target.

The pheromone traps will monitor 'em every week.

Once we get to threshold, we know that they're laying eggs.

So I wanna spray seven days later when those eggs are hatching and the little worms come out and crawl down and try to get into an apple.

So we gotta be very specific about when we're spraying and why.

So those tools altogether, and what we're seeing in the orchard, we use to determine when we're gonna spray, like for insects, in this case.

Fungicides, that's an early spring thing.

The biggest problem with apples is scab.

And for that, the primary season for scab is when the leaves are about a quarter inch through petal fall.

At that time, all the spores are coming up from the leaves from last year and infecting the new growth.

So we wanna protect the trees during that time.

If you protected them through primary scab, we don't have to worry about that scab going from the leaf and onto the fruit.

Because once it gets on the fruit, you get all kinds of nastiness.

- [Mary] Troy, do you have to do anything special for overwintering?

- [Troy] What we do is we will mow the grass really low.

The reason we do that is because there's less habitat for the mice and voles and all those little creatures that like to chew on the trees in the winter.

We'll also put out bait stations after we're done harvesting to keep their populations low throughout the orchard.

But other than that, that's really about all we need to worry about.

- When it comes to harvesting when you have such a huge crop, how do you harvest?

- So we have a picking crew.

We have about, I think 9 or 10 people on that crew at any given day.

They'll come out and they'll pick, you know, 8 to 12 bins.

(tractor rumbling) They'll pick 8 to 12 of them a day, and we can usually get through everything, usually we start, you know, mid to late-August, and run through, you know, early to mid-October.

Just depends on the weather in the fall too.

But you know, the variety's ripen at different times.

So we start with First Kiss, you know, kind of when we're finishing them up.

Then we're getting into our Sweet Tango and our Zestar.

And when those are finishing up, then we're getting into the Honey Crisp, and the Cortlands, and all the other varieties.

So they're really staggered, which is obviously helpful.

If they all ripened at the same time, there'd be no way we could get it done.

- [Mary] How do you know when they're ready to pick?

- [Troy] How do we know when they're ready to pick?

We do a few different things.

My favorite is just taking a bite and seeing how it is.

There's a lot of other indicators we use as well.

You can cut the apple in half and check the color of the seeds.

If the seeds are still a little white, they're not fully brown, it's not ready yet.

We also do starch iodine testing.

Same thing, you'd cut the apple in half, you spray it with a starch iodine solution, and you let it set for a minute so you can kind of see, you know, they ripen from the inside out, you can see where the starches have been converted to sugars and how ripe that fruit is.

And there's different indices of when it is fully ripe.

You know, if you're gonna store 'em for a long time, you wanna pick 'em a little under ripe.

If you were gonna, you know, sell 'em fresh market today, you want 'em as ripe as can be.

So, you know, we use a lot of all those different things.

We also check the bricks of the juice, see what the sugar levels are at as well.

So we do a lot of different things to kind of check that.

But, you know, apples are kind of, it's a ticking clock from when they bloom typically, to when they're ripe.

It's not like corn or other, where if you get some heat, they really grow.

Apples are just kind of, they take their own time, and you know, you can usually have a pretty good idea year after year, when you harvested, when was bloom.

And yeah, so we use all those things and determine when we're ready to pick.

- About how many apples do you get from each tree?

- Oh boy, let's count.

(Mary laughing) It varies, honestly.

I mean, you know, like we talked about biennial bearing.

Some years, you know, like on my Honeys, there's some trees with zero.

Others might have 400 apples.

I've never really counted how many are on each tree at the end of the year, (chuckles) but I mean, I would guess at least a hundred or two.

- [Mary] Can we see what you use all of your apples for?

- [Troy] Absolutely, we can head on over to the pack shed and take a look.

(cheerful music) - I have a question.

We have lilacs in our yard, and this summer, the leaves turned brown and died very early.

What happened?

- We are right there with you at the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum.

Some of our lilacs have not looked great for the last four years.

Unfortunately, this is a new disease to Minnesota called Pseudocercospora Leaf Spot.

I'm not gonna try and say it 10 times fast, it is a fungus-caused disease.

So you do have to get it confirmed in a lab to say for sure.

But chances are, if you have these kind of brown leaf spots or lesions on your lilacs, that's what it is.

It's unfortunately becoming a much more common fungus, especially up in the upper Midwest.

It is favored by humid conditions and moderate temperatures.

And unfortunately when our lilacs break bud in May, that's exactly what we have, we have high humidity with plenty of rain, and we have moderate temperatures.

So this fungus takes off.

Fortunately, it doesn't seem to be affecting every single lilac, but unfortunately it is also affecting most of our lilacs.

So especially the one that's standing right next to me has lost all of its leaves.

They do turn brown, they drop on the ground.

And unfortunately, even on a wet day, you can actually see the spores on the undersides of the leaves.

They will stay on these leaves for the next two years.

So if you have Pseudocercospora Leaf Spot on your lilacs, it is critical that you rake up all of the fallen leaves and dispose of them.

Do not compost them, do not mow or mulch them, but throw them in the garbage, unfortunately.

You need to get rid of them, because that will serve as your source of infection for the next year or two.

You might consider cutting back your lilacs if the branches do appear dead.

It is thought that it's not necessarily going to kill your lilacs, but if you repeatedly lose leaves like this every single year, your lilacs will become weaker and weaker every year, and eventually they might succumb to it.

However, research that we're doing lately at the arboretum with University of Minnesota horticultural experts is to determine which lilacs might be resistant to it.

And as more data becomes available with that, we will better be able to tell you which lilacs you should buy, and which ones you should put in your home so that you can avoid something like this in the future.

- [Announcer] "Ask the Arboretum Experts" has been brought to you by the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum in Chaska, dedicated to welcoming, informing, and inspiring all through outstanding displays, protected natural areas, horticultural research, and education.

- Troy, where do the apples go when they're done from the field?

- So in the field, we have 20 bushel bins that we pick into, and we have a trailer that holds four of 'em.

So when they go out into the field, they'll bring four empty bins, fill 'em up.

Once they're full, they'll come up to this building here.

And depending on the variety, some varieties require different things.

Like for instance, we just did our very first harvest of Honey Crisps, those we leave to sit in here at room temperature for a few days before they go into our cold storage.

So we have a 30 by 40 refrigerator in here, and we also have two reefer trailers outside (vehicle rumbling) that we use as well.

- Okay.

So then how do you store the apples, and how long will they keep?

- You know, how long they keep really depends on the variety.

Once we have 'em up here, they're harvested, we treat them with what's called MCP.

So it's essentially a gas that kind of covers the apples, and it shuts off the ethylene receptors in the apples so they'll slow down the ripening process.

That gets us a little more time out of them when they're in storage.

You know, Honey Crisps and some of the newer varieties, they can last six to eight months in just common storage, whereas a Zestar, maybe six weeks.

So they do vary depending on the variety as far as how long they do store.

- What do you use all the apples for?

(Troy laughing) - Well, you know, interestingly, as our orchard has grown, we've added uses over the years.

Initially, we were using it just for, you know, selling in pies, and we would sell the seconds, and we pretty much got rid of most of our apples that way.

We would peel a lot of 'em at the end of season, and freeze to make pies and other baked goods (equipment clacking distantly) throughout the year.

Two years ago, we started pressing our own fresh cider here.

And the timing was good, 'cause our crop was increasing last year.

Then we added also hard cider, so that's another use for it.

We also dehydrate a lot of apples too.

So I mean between the baked goods, the cider, the hard cider, we sell to some schools, a couple grocery stores.

Typically we're able to utilize our entire crop.

- What is the difference between juice, cider, and hard cider?

- So, you know, in Europe, you know, when they say cider, they're referring to hard cider.

In the U.S. you know, cider is really unfiltered apple juice.

if it's filtered, then it's called juice, but the process is the same for making it, you know, you squeeze the juice out of it, juice would go through a filtration process so it's much clearer.

- [Mary] What is the process of turning the apples into juice or cider?

- So, when we have our apples in our big 20-bushel bins, they go through our wash line.

So they get dropped down into a sanitizing solution.

They'll go up a little elevator, then they get dropped into a spray tunnel where they'll get sprayed with another disinfectant just to remove any pathogens or bacteria on the apple.

Then they get dried, polished, and then they'll get sorted by size.

At that point, we either bag 'em if it's a nice perfect apple to sell in the store, or it will go into another bin as a second, we would call it here.

So it's maybe not so perfect, and it would be a perfect juice candidate.

At that point then, as we pack out, we store all those, and then we'll make cider depending on what our needs are in that week, you know, two, three, four times a week.

So at that point, apples get crushed into a pumice, and they get put into these tanks right here.

And then they get pressurized in there and all the juice flows out, and then it goes to a pump, and into a tank.

Then it'll either get bottled or turned into hard cider at that point.

So we'll bottle the fresh cider to sell in the store, the hard cider will go through a fermentation process, and then we either bottle or keg that to sell here at the store as well.

This is one of our presses right here.

This machine here is our grinder and our elevator.

So the apples that we had talked about, as the seconds will get dumped into that, they come up the elevator, fall to their fate, and get ground up into a very fine pumice to fill this up here.

This is our press.

Once it's full, this gets folded in.

There's a lid that goes on top, and this bladder in here we'll fill with water.

So we hook that just to a standard garden hose and fill that with water, and we do it slowly.

The whole process to finish pressing one of these is probably 25 minutes or so.

So you slowly add water to it.

That bladder fills and pushes out.

The cider will run down the sides of this.

They'll go into that tube there.

This pump runs over here, and it'll drop into a tank over there.

So as we're pressing, it's getting pumped from here over into a tank as they're going.

- [Mary] Troy, why do you add water?

- Water doesn't get added to the cider, that just goes into the bladder to pressurize it and push out.

And that's enough pressure, if it's about 30 pounds, is the top for that.

And like I said, it's about a 25-minute process per tank.

So when one is getting filled and pressing, the other one is getting filled with pumice, and then we empty them, the leftover, you know, pumice that's left in there, and then we use that, and take it out, and spread it in our fields.

- How do you clean this after there are pressings done?

- So there's a whole cleaning process.

I mean really, it's spraying down.

I mean, it's a pretty messy process.

You know, there's kinda stuff everywhere.

It is a dirty job.

But once everything is all cleaned, and been scrubbed, and the the lines will all get, you know, sanitized with sanitizer run through them, we also have a foam sanitizing machine that all the equipment gets sprayed with, and that'll sanitize all the surfaces after they've been cleaned.

- Are there certain varieties of apples that are better for different uses?

- Absolutely, yeah.

I mean, we use three different varieties for our pies, depending on our crop that year and what it looks like, we should utilize the best.

Sometimes we use a mix.

Cider, some varieties are a little more tart, they can give it a little more dynamic flavor to it, some are just all sweet.

So we try to blend them to get something that's got a little tart, a little sweet, and that's got a really good flavor to it.

- How many pies do you make in a year?

- Me, personally, not many.

(Mary laughing) But no.

And when you say pies, we do a couple different pies, we do our fruit pies, and then we also do savory pies.

So I think probably 6,000, 7,000, 8,000 a year that we make.

- [Mary] Do you have special equipment to help you chop up all of those pies and to make 'em into the special things?

- [Troy] We do.

So we have our apple peeler, which, it's a pretty prehistoric looking device.

We have two people, once we kinda get through picking, and harvest is done, then they'll focus on peeling.

So every day they'll, you know, peel and freeze, 400 or 500 pounds of slices.

They'll go in the freezer, and then they'll stay there until the next spring.

We'll start making pies for fall.

So we'll take all those apples out of there, turn 'em into pies and stockpile the freezer before we open in the fall.

- [Mary] So what are your favorite varieties, and why?

- For pies?

My favorite, I think I would have to say, would be Zestar.

I think that one, just for me, it's the perfect flavor.

For fresh eating?

Oh boy, that's a hard one, 'cause I like 'em all.

But if I had to pick one, I'd probably say Sweet Tango, if I had to pick one.

But there's so many other good ones.

Kinder Crisp is another one of my favorites that a lot of people aren't aware of, but that's also an amazing apple.

- Do you sell all of your produce here, or do you provide some for other places too?

- So we sell most of it here.

Our fresh cider, hard cider is all here.

We really don't distribute any of that at this point.

We do sell fresh apples to schools, some grocery stores, other groups, you know, will come to us for apples for different occasions.

And our pies, we do sell them here, and we also sell them at a couple of other locations nearby.

Our hard cider, which we just introduced last fall, really, it was our son that wanted to do that.

He joined us full-time five years ago now.

Every fall, he's been making hard cider.

You know, it started out with one gallons, up to bigger ones, and then five gallons, and now we're into 250-gallon batches at a time.

So the process for making hard cider is, once our cider is pressed, it is ready to go.

At that point we put in an additive to kill any of the wild yeast that is in the apples themselves.

And then after about a day when that's done, then we reintroduce yeast into the cider, and that yeast consumes the sugars in there, gives off carbon dioxide and creates alcohol.

So as it's fermenting, just like a wine would ferment, same process, after it's used up all the sugars in there, then the yeast is kind of done and the product is done.

When I say it's done at that point, it's flat, so there's no carbonation in it.

We usually age ours for about nine months to a year.

The stuff we make this fall will sit in our cooler until next summer, and once we're ready for it, then we'll either put it into a keg and carbonate it, we also add flavorings too, so we use flavorings from our farm here.

(upbeat country music) So we use our raspberries, our rhubarb, our honey berries, our aronia.

So we've used all our different fruits to flavor the cider as it's getting, you know, kegged or bottled.

- [Mary] Fascinating.

- [Troy] And it's really been a good use for our product too.

I mean, you can take those apples that aren't gonna store for very long, and all of a sudden we can turn 'em into a product that does store for longer.

So we have that, you know, ready to go for the following year.

(upbeat country music continues) (upbeat country music continues) (upbeat country music continues) - Well, this has been really, really interesting.

Thanks so much for letting us come and learn all of this.

- Absolutely.

- [Announcer] Funding for Prairie Yard & Garden is provided by Heartland Motor Company, providing service to Minnesota and the Dakotas for over 30 years.

In the heart of truck country, Heartland Motor Company, we have your best interests at heart.

Farmers Mutual Telephone Company and Federated Telephone Cooperative, proud to be powering Acira, pioneers in bringing state-of-the-art technology to our rural communities.

Mark and Margaret Yackel-Juleen, in honor of Shalom Hill Farm, a nonprofit rural education retreat center, and a beautiful prairie setting near Wyndham, Minnesota.

And by Friends of Prairie Yard & Garden, a community of supporters like you, who engage in the long term growth of the series.

To become a Friend of Prairie Yard & Garden, visit www.pioneer.org/pyg.

(cheerful music)

Preview: S38 Ep11 | 30s | Country Blossom Farm near Alexandria, Minn. is a popular destination that produces fine apples. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Home and How To

Hit the road in a classic car for a tour through Great Britain with two antiques experts.

Support for PBS provided by:

Prairie Yard & Garden is a local public television program presented by Pioneer PBS

Production sponsorship is provided by Shalom Hill Farm, Heartland Motor Company, North Dakota State University, Friends of Prairie Yard & Garden, and viewers like you.