Prairie Yard & Garden

Plants Around the World in Minnesota

Season 38 Episode 12 | 28m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

Experience a fascinating range of plant life from different ecosystems.

Experience a fascinating range of plant life from different ecosystems such as Diverse Deserts, Mediterranean Scrubland, the Ancient Rainforest, and the Antarctic Forest, all in one place at the Conservatory in the U of M College of Biological Sciences. It's a captivating journey through the flora of the Southern Hemisphere without ever leaving Minnesota.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Prairie Yard & Garden is a local public television program presented by Pioneer PBS

Production sponsorship is provided by ACIRA, Heartland Motor Company, Shalom Hill Farm, Friends of Prairie Yard & Garden, Minnesota Grown and viewers like you.

Prairie Yard & Garden

Plants Around the World in Minnesota

Season 38 Episode 12 | 28m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

Experience a fascinating range of plant life from different ecosystems such as Diverse Deserts, Mediterranean Scrubland, the Ancient Rainforest, and the Antarctic Forest, all in one place at the Conservatory in the U of M College of Biological Sciences. It's a captivating journey through the flora of the Southern Hemisphere without ever leaving Minnesota.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Prairie Yard & Garden

Prairie Yard & Garden is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

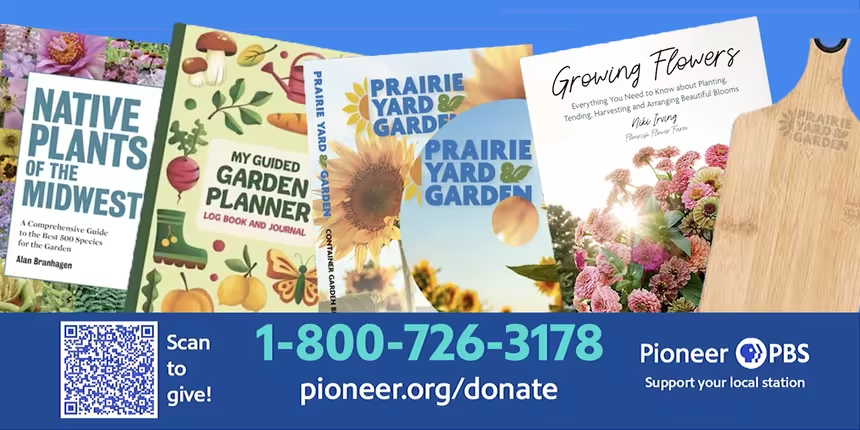

Prairie Yard & Garden Premium Gifts

Do you love gardening? Consider becoming a friend of Prairie Yard & Garden to support this show and receive gifts with your contribution. Visit the link below to do so or visit pioneer.org/donate.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(uplifting music) - When Tom and I travel out of state, we love to look at the plants around us.

If there is a botanic garden near, you can bet we try to make a stop.

In fact, a few years ago, we almost missed our bus tour leaving because we were so busy admiring the unusual plants in that area.

Imagine my excitement when I found out there is a whole greenhouse full of plants from the Southern Hemisphere growing right here in Minnesota.

Come along, we have to check this out.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] Funding for "Prairie Yard and Garden" is provided by Heartland Motor Company, providing service to Minnesota and the Dakotas for over 30 years in the heart of Truck Country.

Heartland Motor Company, we have your best interest at heart.

Farmers Mutual Telephone Company and Federated Telephone Cooperative, proud to be powering ACIRA, pioneers in bringing state-of-the-art technology to our rural communities.

Mark and Margaret Yackel-Juleen in honor of Shalom Hill Farm, a non-profit rural education retreat center in a beautiful prairie setting near Windom, Minnesota.

And by friends of "Prairie Yard and Garden," a community of supporters like you who engage in the long-term growth of the series.

To become a friend of "Prairie Yard and Garden", visit pioneer.org/pyg.

(bright music) - I get a magazine called the Northern Gardener, published by the Minnesota State Horticultural Society.

One of the articles in the magazine was titled A World Under Glass, and it was about the conservatory at the University of Minnesota, and I just had to find out more.

So I contacted Jared Rubinstein, and he said we could come for a tour.

Thanks so much, Jared, for letting us come and ask questions and showing us all of the neat plants here.

- You're very welcome.

Thanks for coming.

- Now tell me about what is the conservatory?

- So this is called the College of Biological Sciences Conservatory & Botanical Collection.

We're part of the College of Biological Sciences here, and we're primarily a teaching resource for departments within that college, which means that we support research and education, not just in the college but really at the entire university.

So we do that in a couple of different ways.

We bring groups into our space for tours and activities.

We bring plants from our potted permanent collection to lab courses for dissection or observation and then any plant material that's used in a CBS lab course.

For an experiment, we grow all that plant material as well.

So we're primarily a teaching tool for the college, but we're also a publicly accessible plant conservatory and a resource for really anyone else at the university.

- [Mary] How long has this been here?

- [Jared] So this facility was open in 2020 and then promptly closed for the pandemic and reopened just last fall to the public.

So this particular facility has only been around for about four years.

Prior to this facility, there was another one on the St. Paul campus that was built in the '70s.

And then before that, we can trace the lineages of these University of Minnesota greenhouses all the way back to the late 19th century when the first greenhouse was built, showing, I think, the university's recognition of the utility of having a live plant that you can touch and interact with and smell.

For students to learn with, there are only so many months out of the year where you can do that outside.

So really since the beginning, the university has shown this understanding of having plants under glass that students can interact with and study.

Most of the plants we have in here are not from the United States.

Most of them are from other parts of the world.

We're trying to show the people of Minnesota what the plants of the world look like, not what the plants of Minnesota look like.

It's very difficult to import live plants into the United States.

It's much easier to import seeds than it is live plants.

So seed collectors can go around the world, get permits, bring those back, grow them, and then distribute plants among other botanical collections.

So some come from other gardens, which is great.

Some come from specialty nurseries that we just buy plants from.

And then sometimes, we can even import seeds from seed nurseries around the world and grow them ourselves.

Once we have a plant, we can just propagate it and get as many as we want as long as it's not too difficult to propagate.

- What is your background, and what do you do here at the conservatory?

- Sure, so I grew up in the Pacific Northwest in Seattle and I moved to Minnesota for graduate school.

I have a master's degree in horticulture from the university from here.

I left for a while and lived in New England and worked at the Arnold Arboretum there and a couple of botanic gardens in Pennsylvania and then moved back here to start working at the conservatory.

So my title is Curator of the Conservatory and I manage the space, I supervise our student staff and I try to keep everything alive.

- How in the world do you keep track of all of the plants that are here?

- [Jared] So every plant should have a tag in it.

We try to keep track of everything by making sure everything is labeled.

We also have a plant records database, so each plant gets a distinct identifying number.

One way to think about it is this is a collection of objects, just like an art museum has a collection of paintings.

Our objects are alive, so this is a living collection.

So we try to keep track of each object as though it's, you know, its own piece of art.

- [Mary] Do you still add plants to the collection too?

- [Jared] We do.

We are limited by space, obviously.

So when we get to capacity, we have to get rid of things before we can add anything.

But we do add plants occasionally.

We have a couple of criteria to help us decide if we can accept a new plant or if we should acquire a new plant.

So if a plant is from the part of the world that we're representing in our biomes, that's one way.

If a plant is particularly useful for teaching or for research at the university, then we'll acquire and keep those plants alive.

Or if there's a plant that's maybe of really high conservation value or helps us round out maybe our taxonomic diversity, then we might try to acquire that as well.

- So when you get a new plant, do you have to keep it in isolation for a little while?

- We usually try to, depending on where it comes from, if we know, you know, the person who it came from and we know maybe they have good practices, we're often trying to avoid introducing any insect pests in some of these plants.

So if we buy things from a local nursery, just because there's so much diversity at nurseries, that's probably the highest risk.

So yes, often we'll keep a plant maybe outside for a little while, we'll try to clean it or examine it.

Worst case scenario, we can apply some insecticides, but usually, we'll just keep it separate for a while until we're pretty confident that it doesn't have any insect pests or sometimes, you know, maybe a fungal disease or a virus that displays, we don't want to introduce that into the space.

- [Mary] So are your plants here grown in pots or in the ground or both?

- [Jared] Both, so our space is divided in half, we have an in-ground half that we'll go to and we've got this potted half that we're on right now.

These plants that are in pots, these are plants that we can move around.

So we can bring these to class, we can bring these to various labs or we can offer them for research.

Plants over here, we can't move.

So those are in the ground.

Those represent biogeographic collections where the plants are from very specific parts of the world only.

And we can tell very specific stories about evolution or plant diversity or ecology.

- [Mary] So the plants on that side, is that what you refer to as biomes?

- Yeah, so each of those rooms is referred to as a particular biome.

So biomes are just parts of the world where the climate leads to a particular population of animals and plants.

So a couple examples of biomes would be a desert biome or a tropical forest or a temperate forest.

Those are different kinds of biomes.

So we've divided up the conservatory into some of these different biomes around the world and then tried to select geographic areas where those biomes are duplicated but in different parts of the world to show, again, the people of Minnesota what plants and those biomes look like different from our biome here in Minnesota.

- Oh, Jared, can we go look at those?

- Yeah, of course.

(bright music) - I have a question.

The plants in my yard are dying.

I suspect I'm not planting the right plants.

Where do I go for advice to select the right plant for the right place?

- So how many people think they have brown thumbs because their plants die all the time?

The problem is not the plant, it's actually selecting the right plant for the right place.

And the best way to do this is to truly understand the growing conditions that you have in your own backyard.

So here, we're standing in the Bailey Shrub Walk.

We're in front of these amazing hydrangeas.

Clearly, they are doing very well here.

They're in full sun, they have well drained soil, their roots are mulched and they have plenty of room to get to their full mature size.

So sunlight is important.

The space that you have for the plant to grow to its mature size and form and then also the type of soil that you have.

Now, how do you find out about the soil?

You can send a soil sample to our soil test laboratory at the University of Minnesota on the St. Paul campus and they can test your soil and send back a full report so that you know what you're working for as a foundation to your landscape.

You can also judge the light by simply observing it in your location in your backyard and determine whether you have full sun, which is eight hours or more of full sunlight, or maybe you have part shade and that's three to six hours of sunlight in that space.

And then the space itself, you just measure it, get out your measuring tape, have a buddy over, measure the space so you can understand how wide the plant should be and then how tall the plant should be too.

You don't wanna block any windows or doors.

Now there's a lot of other features that you can also search for plants for.

And how do you get that information?

The University of Minnesota Yard and garden page from extension has a great plant database called Plant Elements of Design.

Brand new version came out in 2024, and it's really a top notch way to enter in all these features that you want in a plant as well as your growing conditions.

Click Search and any and all plants that match from the 2,700 plus plants in this list, it's gonna come up and you can search through those and determine which kind of plants that you can grow in your backyard.

- [Narrator] Ask the Arboretum Experts has been brought to you by the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum in Chaska, dedicated to welcoming, informing and inspiring all through outstanding displays, protected natural areas, horticultural research and education.

- So Mary, this is what we call our antarctic forest.

This is a temperate forest biome.

So the plants in here are from very specific parts of the world only.

On this side of the path, we have plants that are all New Zealand and Tasmania.

And on that side of the path, these plants are all from southern Chile.

So those are two parts of the world that have this temperate forest climate, which means that it doesn't get very hot in the summer and it doesn't get very cold in the winter.

If these plants were outside in Minnesota, it would be both too cold and too hot.

So they really need that kind of temperate, middle temperature.

- [Mary] Jared, how in the world do you keep them cool in the summer and warm in the winter?

- The biggest challenge for us is keeping them cool in the summer.

In the wintertime, we can just turn the heat on and it gets as hot as we need it to be.

In the summertime, cooling down a glass building when the sun is beating down and it's 105 degrees outside is very difficult.

The ways that we try to do that are by using these vents that are along the side of the building here.

These are evaporative cooling units or swamp coolers.

So that's chilled water, that air blows over and cools down and then the very top of the greenhouse, the roof will open up and let air out so we can blow cold air in and hopefully, push hot air out.

If everything is working the way it's supposed to work, then we can usually get this room to be about 10 to 15 degrees cooler than it is outside.

These plants really don't want it to be more than about 75 degrees.

So in the summer, if it's 110 degrees, we're not quite there, but we're closer than any other greenhouse that we can get.

So these plants really need that cool climate.

And they're adapted to those very temperate kind of middle ranges of temperature.

So the story we like to tell in this room and in these two parts of the world are about plants that grow both in southern Chile and in New Zealand and Tasmania that are very closely related to each other.

And we try to get students and visitors to think about how that's possible.

So for example, we've got a tree on this side of the room that's in the genus Podocarpus.

We have another plant on this side of the room in Chile that's in the same genus, which means that they share a common ancestor.

They came from the same place and yet they're growing on opposite sides of the world.

So we try to get students to think about the fact that they weren't always on opposite sides of the world and instead we're part of the same super continent and eventually split apart.

So plants that were growing in those two parts diverged and evolved away from each other, but they share common ancestors.

So we have lots of examples on both sides of the room of plants that are maybe the same genus or sometimes the same family, or even the same species that grow in these very different parts of the world.

So we have examples of ferns that grow in New Zealand and we have examples of ferns that grow in Chile that are in the same genus or even sometimes the same species.

All of these plants are adapted to these temperate climates, so we'll often see them be evergreen 'cause it's not super hot or super, super cold.

So they're photosynthesizing year round.

One of my favorite plants is this one right here.

This is a very unusual plant called Pseudopanax ferox.

It grows in New Zealand and if you look at it, it almost looks like it's dead, but these are its leaves, these hard, sharp, jagged leaves.

They've evolved leaves like this to try to avoid being eaten by an animal, that's called herbivory.

A lot of plants that have these kinds of spines or really tough leaves, that's to prevent herbivory.

This particular plant is thought to have co-evolved alongside a giant flightless bird in New Zealand, sort of like an ostrich.

So it has these leaves specifically to try to stop this bird from eating it.

What's very unusual is that when this tree gets to be about eight or nine feet tall, so little taller than me, it'll stop making these leaves, which are very energy intensive and resource intensive to produce.

It'll stop making these leaves and just start making more normal looking broad leaves like you might see on another tree.

And it's because we think that bird could only reach so high with its beak.

And this plant has evolved to stop spending energy on these leaves that it needs to protect itself from being eaten once it's outta the reach of the bird, which is very unusual.

So when this gets to be taller, we'll start to see some of those new leaves.

And once we're there, we'll have to get another one that's smaller, so we can show both examples of these kinds of leaves.

But if you look around the room and really around the world, we have very, very few examples of plants that have multiple types of leaves that it's producing at different heights.

This is one of those examples, and it's exciting plant for us to have in here.

- These look like strawberries.

- They are strawberries, yeah.

So this is a species of strawberry that grows along the Pacific coast called Fragaria chiloensis.

And it's actually one of the parents of the strawberry that we buy in the grocery store, which is a hybrid between two different species.

So one of them is this Pacific coast strawberry that grows in Chile and along the coast of South America all the way up to California.

The other parent is an eastern strawberry that grows in eastern North America, Fragaria virginiana.

So the modern strawberry that we buy in the grocery store is a hybrid between this west coast strawberry and this east coast strawberry, which if you think about it, never hybridized on their own because the Rocky Mountains are in the way.

So instead it was an accidental artificial hybridization that happened in a garden in France of all places from a botanist who happen to have both of these growing in his garden.

They accidentally hybridized, grew a very delicious fruit and that's where we get the modern strawberry.

Well, you can see that it's flowering, which is the first step towards fruiting.

But because we don't have pollinators in here, we don't have bees flying around.

They're not pollinating on their own.

We've tried to pollinate them by hand, but it just doesn't work as well.

So we've never gotten a strawberry that we could eat.

- [Mary] And here I see a plant that says fuchsia, but these don't look like the fuchsias in my garden.

- Right, so this is a ground cover fuchsia, a low creeping fuchsia, Fuchsia procumbens is the Latin name.

And this grows in New Zealand.

And this is one of those examples of a plant that has a sort of cousin on the other side of the world and really all throughout the world, this is a New Zealand species of fuchsia.

On our Chilean side, we have a more traditional shrubby looking fuchsia called Fuchsia magellanica.

These are examples of plants that share a common ancestor that were growing on a super continent and over millions of years and thousands of miles apart have diverged, and now we have a creeping ground cover type of fuchsia instead of the one we're more familiar with here.

So now we're in what we call our ancient rainforest.

This is a tropical rainforest biome, which means that it's always warm in here and it's always humid year round.

So winter, summer, it's always warm, it's always humid.

All of the plants in this room are from a very unusual island called New Caledonia, which is off of the east coast of Australia.

And it has a lot of unusual characteristics because it's an island, it just sort of has a different kind of flora.

And one of the things that makes New Caledonian plants really special or its tropical forests really special, is that it has some of the only remaining tropical forests that still have a lot of conifers in them.

So if you think about tropical forests around the world, you know, we think about birds of paradise or hibiscus, these big flowering plants, cone bearing plants, which evolved earlier than flowering plants, used to grow in the tropics all over the world.

But when flowering plants evolved, they sort of took over the tropics.

So it's very unusual to have a tropical forest that still has conifers, but we can find one in New Caledonia.

So this plant right here, which is a favorite, is an example.

This is Araucaria from the family Araucariaceae.

This is a conifer species and family that's very poorly represented in the northern part of the world where we live.

So this is an example of a tropical conifer that's related to, you know, pines and spruces and furs and plants like that.

But it's one that only grows in the tropics, so it'll make cones instead of flowers.

And you can see throughout the kind of background here, we have a few different examples of these tropical conifers.

- That's so neat.

Well, what are some of the other cool plants here?

- Across the path here, we have some really special plants.

Another thing that makes New Caledonia really special, these plants are called Amborella trichopoda.

And they are special because in the tree of life, if we look at all the flowering plants, these plants are the oldest still living flowering plant, which means that anything that evolved flowers before these Amborella are extinct and we only know about them through fossils.

So these are as far back as we can go in the tree of life to see a living flowering plant, which means, again, with these, you know, ancient conifers that grow in a way that we don't see them in other parts of the world, and then these oldest possible flowering plants, New Caledonia has these really ancient lineages of plants.

And for botanists and researchers, it's a really exciting place to get to study, 'cause it's sort of a way to see what maybe the world's flora used to look like in an earlier era.

Their flowers are very small and white and sort of uninteresting, and it's because they're so ancient.

They haven't evolved some of the different parts like the pistils and the stamens that are as differentiated as we might expect to see on a more modern flower.

But they do flower, and we've even been able to get them to fruit and we've been able to collect seeds out of those fruits and germinate new plants.

This room we call our Mediterranean scrubland.

So this has a Mediterranean climate, even though the plants from here are not from the Mediterranean sea region, Mediterranean climates are climates that have hot and dry summers and cold and wet winters.

So in here, what that means for us is we're in the springtime, we're about to go into our summer, which means we'll induce an artificial drought and we see plants in here that have to be able to survive that summer drought.

In the fall, we'll start to water a little bit more, it'll get a little cooler, and then we'll have a smaller dormancy in the winter.

In the springtime, we'll water, it'll start to warm up, and we'll see this great flower show.

But in the summer, all of these flowers will drop down and all of these plants have to go dormant and really be able to survive that kind of drought.

So what we try to get students and visitors to think about in this room is really to compare where we just were in the rainforest to the way the plants look in here in a Mediterranean climate because the big resource difference in the summertime, obviously, is water.

These plants don't have as much water in the summer and we can really just physically see how different they look as a result.

We can see plants that are much lighter in color.

So for the same reason that we wear light clothes in the summertime, sometimes plants will have lighter leaves to reflect light off of them.

Often we see plants in these kinds of regions that are lower to the ground and more spread out, and that helps shade the ground around them and hold water in the ground for longer to kind of make water be available for a longer amount of time.

And we even see much smaller leaves specifically, that has to do with trying to maximize photosynthesis, which is happening from the leaf, and minimize the amount of water that's lost during photosynthesis by getting just the right amount of surface area.

Whereas in our tropical room, we saw much larger leaves, much darker green, much thicker leaves where water will run off of the leaf instead of plants in the tropics are worried about rotting from too much water.

Whereas plants in here, they're trying to grasp every little bit of water that they can.

So we can just see by looking through the window in a way that you can't do, you know, in the wild what these two different biomes look like.

And if you take away water in the summertime, how different the plants might look.

Because it's springtime in here, and again, in the fall, this is sort of the best time to visit because this is when we see most of our flowers.

A lot of these plants are bulbs in the Amborellaceae family or the iris family or the lily family.

And after they're done flowering and after the summer drought starts, they'll drop their flowers, they'll drop their leaves, and they'll just kind of go underground and wait out the summer drought.

So this room is divided in half by our path.

On that side of the path, all of these plants are from the southwest coast of South Africa, so the Cape Provinces, and on this side of the path, all of these plants are from the southwest coast of Australia.

So again, two parts of the world that are very far apart, but that both have this Mediterranean climate.

We have lots of unusual cool plants in here, including these carnivorous plants in some of our bogs on both sides of the path.

Carnivorous plants, primarily we have sundews in here, which are carnivorous plants that attract insects.

They get stuck to its leaves and then they have specialized enzymes that break down the insects into nutrients that they can use.

We have one example over there of a different path where this plant doesn't have those specialty enzymes.

And instead it's evolved this mutualistic relationship with a beetle where the insects will get stuck to the plant and instead of the plant just breaking the insects down, instead it waits for this beetle to come along and eat the insects, after which the insects have to go to the bathroom.

And the plant has specialized enzyme that break down the waste that come out of the beetle.

So it's added this extra step unusually from all these other carnivores plants.

So this is our diverse deserts room.

This is a desert biome, so it's hot and dry all the time, winter, summer.

It's just hot, it's dry.

We don't have any misters in here, so low humidity all the time.

The plants in here are from three different deserts in the world.

On our north side there, we have plants from Northern Brazil.

On this side, we have plants from the Horn of Africa, so that's Somalia, parts of Ethiopia and Eritrea.

And then in the center here, we have an island with plants from the island of Socotra, which is an island off of the Horn of Africa in the Indian Ocean.

These are three different desert environments around the world that all have this kind of hot, dry environment.

In here, we try to talk a little bit about adaptations to the desert.

So the big difference between our desert room and our Mediterranean room is that though there's a summer drought in there, there's plenty of rain in the winter.

And here there's no rain in the winter.

So these plants are always going through this hot dry period.

So this plant is a good example of a desert plant.

This is a euphorbia that has a couple of characteristics we see throughout the room.

So you can see it has really small leaves.

Those are to try to reduce the amount of water lost during photosynthesis and to make up for that, it's got green stems, which means that the stems themselves are photosynthesizing.

The stems are also really thick and fleshy, which means they're storing water inside of them.

So, you know, those are characteristics we see throughout the desert.

So this is a euphorbia, and it's got that characteristic.

Right next to it, we have a plant that's actually in the grape family, and this has very similar characteristics.

So if we look at this one, you know, it doesn't look exactly the same, but it still has these long, thick green fleshy segments and it doesn't have leaves.

And then just next to it on the other side, we have a plant that's actually in the milkweed family that also looks very similar.

So we've got milkweeds, euphorbia, and grapes that are not closely related to each other, but they're all evolving the same adaptations to survive in the desert.

So throughout the room, we see other examples of that.

You can see plants that have these really thick, swollen bases.

Those are called cortex bases.

Those are also storing water.

So we see that across families.

This is the mulberry family or the milkweed family, or even the cucumber family.

We see some of those examples throughout the room.

Other things we always see in here when we think about a cactus, for example, are the spines, right?

And that often this has to do with trying to prevent an animal from biting a plant.

And when the plant is bitten open, it loses water.

- What is this plant back behind us here that's so unusual?

- [Jared] Yeah, so this is actually frankincense which grows in the Horn of Africa.

And if you break it open, it produces this exudate that has a very strong aroma and that's where the frankincense scent comes from.

- This has been absolutely marvelous.

Is this place open for tours?

- It is, yeah.

So the side that we're on, this biogeographic side, this is open to the public every day during the week from 9:00 to 3:00.

And we're also open for guided tours by request so they can reach out to us directly over email or visit our website to request a tour.

(gentle upbeat music) - [Mary] Thank you so much for this wonderful knowledge and visit.

This is so great.

- Great, you're very welcome.

Come back anytime.

(gentle upbeat music) - [Narrator] Funding for "Prairie Yard and Garden" is provided by Heartland Motor Company, providing service to Minnesota and the Dakotas for over 30 years in the heart of Truck Country.

Heartland Motor Company, we have your best interest at heart.

Farmers Mutual Telephone Company and Federated Telephone Cooperative, proud to be powering ACIRA, pioneers in bringing state-of-the-art technology to our rural communities.

Mark and Margaret Yackel-Juleen in honor of Shalom Hill Farm, a non-profit rural education retreat center in a beautiful prairie setting near Windom, Minnesota.

And by friends of "Prairie Yard and Garden," a community of supporters like you who engage in the long-term growth of the series.

To become a friend of "Prairie Yard and Garden", visit pioneer.org/pyg.

(upbeat music)

Plants Around the World in Minnesota

Preview: S38 Ep12 | 30s | Experience a fascinating range of plant life from different ecosystems. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Home and How To

Hit the road in a classic car for a tour through Great Britain with two antiques experts.

Support for PBS provided by:

Prairie Yard & Garden is a local public television program presented by Pioneer PBS

Production sponsorship is provided by ACIRA, Heartland Motor Company, Shalom Hill Farm, Friends of Prairie Yard & Garden, Minnesota Grown and viewers like you.